Article taken from here

Entering the Sufi Spiritual World of North Africa

Sufi Brotherhoods and Trance Ceremonies in the Maghreb

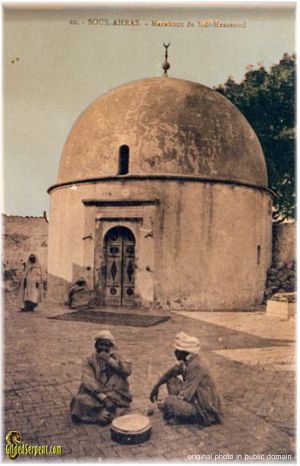

This zawiya is in Souk Ahras in East of Algeria, sometimes

people call the zawiya a marabout – they really mean the

saint. It happens that meals are offered to the poor

every Friday of the week, here we see in the middle of

the picture people sitting and eating bread, on the left

of the picture a man is standing, he is the caretaker.

by Amel Tafsout

posted October 20, 2013

Since antiquity the Maghreb has been a crossroad for people, ideas, movements, humanity and spirituality, where Africa meets the Orient. Although Sufism began to be recognized as a distinctive spiritual path in the 9th Century, separate orders or Tariqat didn’t begin to emerge until the end of the 11th Century, and flourished in the region in the 13th Century. Each Tariqa, usually named after its founder, created its own doctrine, traditions and social conventions. Thus the Shadhiliyya is named after Abu al-Hasan al-Shadhili, the Qadiriyya after ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani, and the Jazuliyya after Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli, whose influence of North African Sufism began on the wider Islamic world in the 15th-17th centuries. Special attention is given to Jazuli’s attachment to two traditions of international Sufism, the Shadhiliyya of North Africa and the Qadiriyya. These networks extended throughout the Islamic world from Afghanistan to Morocco.

Furthermore, the Maghreb consists of many Sufi-brotherhoods, often recognized and set through their Zawiyas and initiations. Sufis have always worked toward reform through advice and education of the individual and internal purification through providing a model and example of tolerance, solidarity, brotherhood and selflessness removed from anything that would give a bad image of Islam.

This zawiya is also a mosque in the center of Algiers, called Sidi Abd Ar- Rahmane

mosque, it is the name of the saint, people come from everywhere to pay their

respect and have a pilgrimage, as the Saint or Marabout was known for healing

diseases)

This is a typical zawiya located in the cemetary in Monastir in Tunisia.It is common

that people pay their respect to their deceased loved ones and also to the saint of

this zawiya)

However, the zawiya is an Islamic religious school, monastery or a religious site, which groups Sufi followers around a particular sheikh. Sufism is based on the Qur’an and the practice of the Prophet. Sufi teaching stresses mysticism and love of God. Sufism purifies hearts and directs intentions towards God. All Sufi orders have certain specific rules and regulations to achieve this realization, and there are particular spiritual states and stations in Sufism that may be obtained by performing certain practices and rituals. At the initiation ceremony, the sheikh who has experienced union with God and annihilation of self, in addition to giving the disciple the special garment, also gives him a secret word or prayer to help him in his meditation.

Sufis also believe in spiritual guides who reveal themselves to the Sufi in visions or dreams and help him on his path. The initiate has to learn spiritual poverty (faqr), which means emptying the soul of self in order to make room for God. The illusion of the individual ego must be erased by humility and love of one’s neighbor. This is attained by a rigid self-discipline that removes all obstacles to the revelation of the Divine Presence.

The struggle of Sufis for the purification of intention towards God leads them to formulate specific practices, and over time these become an indispensable part of Sufi teachings. The saints are not calling for anyone to believe in them despite their visions and blessings. The initiation into a Sufi order is a necessary ritual that transmits the spiritual blessing (Baraka, spiritual power) of the guide (murshid) to the disciple (murid).

Sufi Brotherhoods in the Maghreb

In the Maghreb, most Muslims follow the Sunni Maliki School. A strong tradition of venerating marabouts and saints’ tombs is found throughout the Maghreb and therefore in many places. Rhythms and music styles are named after the marabouts. A network of zawiyas traditionally helped proliferate basic literacy and knowledge of Islam in rural regions. Each Sufi order or a Tarīqa has a silsila that means a chain or a lineage of a specific sheikh of a Sufi brotherhood. The Maghreb consists of various Sufi brotherhoods which are as follows:

This lady is the muqadma or the shawwafa, which

means the medium or the shamman who can

communicate with the spirits and give messages.

She is also in charge of the tomb or the shrine of

the saint. She is here standing next to the shrine

and will make sure that the shrine is respectedby

the visitors. This shrine is located in Tlemcen(In

the west of Algeria and belongs to the Qadiriya

Sufi Brotherhood)

Photo courtesy of VitamineDZ.com

1. Al Qadiriya:

It is the oldest and most widespread order. It has branches all over the world that tie to its center in Baghdad. It was founded in Baghdad by ‘Abd al Qadir Jilani (d.1166) who is considered to be the greatest saint in Islam. It later became established in Yemen, Egypt, Sudan, the Maghreb, Central Asia and India. The Qadiriya stresses piety, humility, moderation and philanthropy and appeals to all classes of society. It is governed by a descendant of al Jilani who is also the keeper of his tomb in Baghdad which is a pilgrimage center for his followers from all over the world.

2. Ash Shadiliya:

It was started by al Shadili (d.1258) in Tunis. It flourished especially in Egypt under ibn ‘Ata Allah (d.1309) but also spread to North Africa, Saudi Arabia and Syria. It is the strongest order in the Maghreb where it was organized by al Jazuli (d. 1465) and has sub-orders under other names. The Tariqa Ash Shadiliya stress the intellectual basis of Sufism and allows its members to remain involved in the secular world. Their disciples are not allowed to beg and are always neatly dressed. They appealed mainly to the middle class in Egypt and are still active there. It is said that the Shadiliya were the first to discover the value of coffee as a means of staying awake during nights of prayer!

3. Al Jilaliya:

This order is a Qadiri branch in the Maghreb who worship al Jilani as a supernatural being, combining Sufism with pre-Islamic ideas and practices.

4. Ad Daraquiya:

It was founded in the early 19th century by Mulay ‘Arabi Darqawi (d. 1823) in Fez, Morocco. It was the driving force behind the Jihad movement that achieved mass conversions to Islam in the mixed Amazigh (Berber), Arab, and Sub-Saharian African lands of the Sahel. It is influential today in Mali, Niger and Chad and still widespread in Morocco.

This is a book cover representating the

Saint Sidi Tijani with his animal-

here the deer – as each saint/marabour

can be represented by an animal,

the mosque behind him is his zawiya.

5.Tijaniyya:

It is the largest tariqa in West Africa whose founder, Ahmed al-Tijani (d.1815), lived and was buried in Fez. Indeed it was a Tijani who was responsible for propagating the Khalwatiyya order, which he had encountered in Cairo on his way to Mecca to perform the Hajj. In a further example of the inter-connectedness of the brotherhoods’ histories, Tijani had also been an initiate of the Wazzaniyya and the Qadiriyya.

6. Al Aïssawa

This tariqa is a religious and mystical brotherhood founded in Meknès, Morocco, by Muhammad Ben Aïssâ (1465–1526), best known as the Shaykh Al-Kâmil, or “Perfect Sufi Master”. The terms Aïssâwa (`Isâwa) is derive from the name of the founder, and respectively designate the brotherhood and its disciples (fuqarâ, sing. to fakir, literally: “poor”). The Aïssawa followers are known for their spiritual music, which generally comprises songs of religious psalms, characterized by the use of the oboe-ghaita (similar to the mizmar or zurna) accompanied by percussion using polyrhythm.

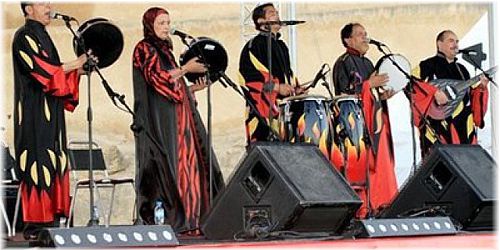

This picture shows the Aïssawa brotherhoods with the leader Said Guissi’s

Ensemble from the holy city of Fes, Morocco. They are considered the most

accomplished groups to emerge from the centuries old Aïssawa Tariqa.

Here they use trumpets and pipes creating a trance – inducing wall of sound.

I met them in London many times at the Music Village festival in 1998 and

also at the Sufi Festival in London in 2000.This picture was taken at the Muslim

Voice festival in 2009 in New York City. They are bringing to life the Sufi

musical tradition of connecting with the Divine.

Complex ceremonies, which use symbolic dances to bring the participants to ecstatic trance, are held by the Aissawa in private during domestic ritual nights (lîlat), and in public during celebrations of national festivals (the moussem, which are also pilgrimages) as well as during folk performances or religious festivities, such as Ramadan, or mawlid, the “birth of the Prophet.” The Moroccan and Algerian States organize these festivities.

In Morocco, the ceremonies of the Aïssâwa brotherhood take the form of nightly rituals (known simply as “night”, lila), organized mainly by Imam Sheikh Boulila (Master of the Night) at the request of women sympathizers. Women are currently the principal customers of the orchestras of the brotherhood in Morocco.

As the Aïssâwa is supposed to bring to people blessings (baraka), reasons for organizing a ceremony are varied and include celebration of a Muslim festivity, wedding, birth, circumcision, or exorcism, the search for a cure for illness, or to make contact with the divine through the extase. Rituals have standardized phases among all the Aïssâwa musin ensemble. These include mystical recitations of Sufi litanies and the singing of spiritual poems along with exorcism, and collective dances.

| A moussem is a religious festival celebrating here the Saint Sidi Ali, known for healing people, therefore this sacred site became a gathering for people to dance and get into trance in order to get healed. |

According to Aïssawa lore, this ceremony was not established nor even practiced at the time of Chaykh Al-Kâmil. Some members of the brotherhood believe that it emerged in the 17th century at the instigation of Aïssâwî disciple Sîdî `Abderrahmân Tarî Chentrî. Alternatively, it may have appeared in the 18th century under the influence of Moroccan Sufi masters Sidî `Ali Ben Hamdûch or Sidî Al-Darqâwî, who were both well known for their ecstatic practices.

More broadly, the actual trance ritual of the Aïssâwa brotherhood seems to have been established progressively through the centuries under the three influences of Sufism, pre-Islamic animist beliefs, and urban Arab melodic poetry suchas the Malhun.

7. Al Wazzaniyya:

Like the Charqawiyya, it is are an offshoot of the Jazuliyya-Shadhiliyya. The tariqa was founded by Moulay (saint) ‘Abd Allah al-Sharif (d.1678), who had been a member of the Jazuliyya order and, unlike the others, takes its name not from their master or founder but from the town in which they are based, Wazzan. This town is located in the southwestern Morocco and founded by al Sharif in the first half of the 17th Century. It is known by many Moroccans as “Dar Dmana” (The Abode of Protection).

8. Al Siqiliyya:

Al Siqiliyya are an annex of the Khalwatiyya. Based in Morocco since the 18th Century, it has also been suggested that they may have some link to Sicily, which had a sizeable Muslim population until the mid 13th Century, and in fact was ruled as an Islamic emirate (called Siqlliyya) from the mid-10th Century to the end of the 11th. The connection between Sicily and Morocco, and Fez in particular, seems to be the role played by Jawhar al-Siqilli (d.992) in the Fatimid conquests of the Maghreb.

The M’alma (master) Zaida Gania is here performing a Sufi song with the female ensemble singing and

playing percussion at the Gnawa festival of Essaouira, Morocco.

Chrib Attay 2009

9. Al Gnawa:

The Gnawa Brotherhood exists under the names of Gnaoua, Ouled Sidi Blel, L’Aabid, Stambali, Zar, etc…

The Gnawa (sing. Gnawi) refers to an ethnic Sufi religious order. The name may originate from the Saharan Amazigh (Berber) dialect word aguinaw or agenou, meaning “black men”. This word in turn is possibly derived from the name of the city significant in the 11th century, in what is now Western Mali, called Gana in Arabic Ghana .The term “Gnawa” has two meanings: It refers on one hand to an ethnic minority of former black slaves brought from Sub-Saharan Africa (especially West Africa: Ghana, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Mali) more than 900 years ago to the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritana); and on the other hand to an even smaller group of people within this ethnic minority who take part in the Lila or Derdeba ritual ceremony of spirit possession. The members of this group have preserved their traditions through the centuries. While they have retained many of the customs, rituals and beliefs of their ancestors, their music and dance are the most preserved traits. After their conversion to Islam they adopted the first black person to convert to Islam and become the first muezzin, Bilel, as their ancestor and saint patron.

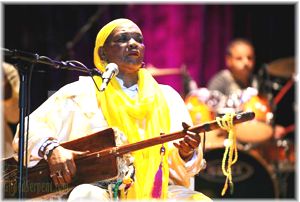

The female Gnawa master M’alma Hasna al Bacharia is

performing here with an electric guitar a Sufi song praising the

prophet Muhammad and the saints. Her ensemble is playing

traditional gnawa 6/8 rhythms.She was featured on the

Algerian National Television channel ENTV.

This picture shows the Master Ma’alma Hasna playing

Gimbri and singing on stage.

The Gnawa of Morocco

During the last few decades, Gnawa music of Morocco has been modernized and therefore became more profane. However there are still many lilat organized privately, which conserves the sacred, spiritual status of the music.

Today Gnawa musicians do not consist of only men; women are becoming respected musicians and still are muquadmat or Shawwafa who are communicating with the spirits. However, they also decided to play the religious instrument, called the gembri. The Haddarat Zaida Gania is a group of women who have learned the female art of oral tradition of the Hadra (zikr) from their mothers and female ancestors. I met them in the Moroccan city of Eassaouira while I was working at the Oasis Dance Camp in Morocco in 2011. They perform Sufi and Gnawa music. I was blown away by their performance and I hope I will find the opportunity to bring them to the United States.

The first ever master female gembri player is called Hasna al Bacharia. Hasna El Bacharia has an artistic career of over thirty years. She mixes the sacred and the profane; she also plays electric guitar, ‘ud , banjo and especially Guembri (a spiritual instrument that is not supposed to be touched or played by a woman).

This picture was taken in Essaouira during the Oasis Dance

Camp, Nov.2011 at the Haddarat Gania’s home. After they

cooked for all of us, they perform for us. Here I am with them as

they insisted that we should take a picture together and there

is another member of ADC present. They are all related and

they are starting to enjoy their success). click for enlargement

Here are the younger Haddarat in performance

Photo courtesy of Mario Scolas. click for enlargement

She is the daughter of one of the masters of the Diwan in the South Western Algerian city of Bechar. In 1972 she founded her first music band with four other female musicians. The band started performing in weddings for only women. In 1976, Hasna and her female ensemble were featured in a huge concert in Bechar by the Union of Algerian Women. In January 1999, Hasna arrives in Paris after being invited by the Cabaret Sauvage at the festival of Algerian Women. After her first successful album, Hasna is invited at many concerts and music festivals around the world. I personally saw her perform many times in London, U.K. We became friends through interesting circumstances and I am always happy to hear that she is rewarded and respected for her art.

While adopting Islam, Gnawa continued to celebrate ritual possession during rites where they are devoted to the practice of the dances of possession, called jedba, and proceed the lila ceremony that is animated by a master musician (M’aalem) accompanied by his troupe. Gnawa music mixes classical Islamic Sufism with pre-Islamic African traditions, whether local or sub-Saharan. The Gnawa use their music and dance to heal the pain of captivity. They perform trance ceremonies called Derdeba (possession rite) which generally takes place at nighttime, for this reason it is called a lila.

The Gnawa believe that many misfortunes that happen to people are not just accidental but Djinns could cause them. That is why some people are under the affliction of some illness, infertility or depression; therefore they come to seek the help of the Gnawa.

Many modern Western scholars see parallels between African American music such as the blues, that is rooted in Black American slave songs, and Gnawa music as well as a Sufi Tariqa.

This influence resonates from other black groups such as the Bori in Nigeria, the Stambouli in Tunisia, the Sambani in Lybia, the Bilali in Algeria and those outside Africa such as the Voodoo religion, the Candomble in Brazil and the Santeria in Cuba.

Sidi Blel

Sidi Blel is a Sufi brotherhood in Algeria that is also related to the Gnawa. The ceremony takes place during a Waâda at a zawiya often led by a sheikh but the Zikr is often recited by scholars called Tolba. The dances Kouyou, the Tbal (a bass drum) and Karkabou (North African castanets) as well as the music called Dîwan are performed by music Gnawa or Sidi Blel troupes. The ritual Tabyette consists of bringing a bull who will be taken with the Sidi Blel musicians around the city with a flag of the Sufi brotherhood before it will be offered as a sacrifice to the Djinns.

There might be that many other animals such as a sheep, a ram or a rooster will also be sacrificed after a prayer. Following this ritual, the dance called Dendoune is performed by the same musicians or sometimes if the celebration is part of a Di\wan festival other music ensembles will perform and end the festival with a dance performance of a Kouyou.

The brotherhood Sidi Blel is named after the first slave freed at the beginning of Islam who became the first Muezzin during the prophet Muhammad’s time.

The Karkabou, the Gumbri and the Tbol (or Tam Tam) are the traditional instruments that represent this brotherhood. The ceremony is called Dîwan or Dîwan Gnawa. It starts with the Tbol and the Karkabou, accompanied by the chanting and the dance. The duration of this performance is around one hour, then the musicians sit down in a semicircle around the M’aalem who is playing the Gumbri and invoking a chant in a choir that is praising Allah and his prophets as well as the saints. The dancers, who are dancing barefoot, are the followers. The Dîwan ceremony starts at the sunset and can end at the sunrise. Many festivals in the year exist in Algeria as a tribute to the sacrifice of the bull, also called Derba. The repertoires of the traditional dances are: Koyou, Bania, M’Bara, Megzaoua, Sergou, Jaiba, Marou.

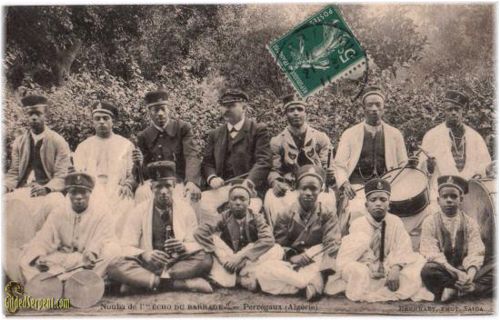

This picture shows a colonial postcard where the Gnawa/Sidi Blel musicians were used in an ensemble for

street music even if they are playing their traditional instrument and in the middle of the picture sits a

French Colonial who is their leader. Note that they are in the same time soldiers for the French Army as

they are all wearing a kind of the French Kepi hats

This is another typical Colonial postcard showing the Gnawa musicians from Casablanca with their traditional

instruments. It is interesting that they are called Indigenous musicians, because every person who was

not French was called Indigenous at that time.

The instruments The Karkabou castanet and the bass drum called T’bol

Ga’ada Diwan Béchar with the ensemble Ferda “Benbouziane”, |  This a poster for the Gnawa Festival in Algeria called Diwan, |

This is a unique video of two amazing music ensembles of the Algerian Southern city of Bechar performing together a Sufi song calling | |

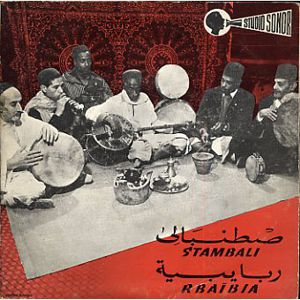

As Stambali or Stambouli

Stambali is a ritual of possession in Tunisia, using music as a healing form. This ritual came from Sub-Saharan Africa where music, chanting and dance enable people to get into a trance and embody supernatural entities. The term designates generally a series of practices where the Stambali is the last phase, with a healing vocation or a conspiracy of the Evil Eye. Stambali gathers elements originating from Africa and the Maghreb

It is a ceremony where mostly Black Tunisians (former slaves) take part and where dance and instrumental sounds are associated to African rhythms. This ceremony is very similar to the Haitian Vaudou or the Brazilian Candomblé.

This LP cover shows the Tunisian Stambali musicians with the whole ritual setting of the Derdeba with incense and instruments. | This video from the Tunisian Television shows a Hadra/Zikr by a Sufi Brotherhood. |

Hadra

Haḍra means “presence” in Arabic. It is a collective ritual performed by Sufi orders in a zawiya, a mosque or at home. It is often held on Thursday evenings after the night prayer. The hadra features various forms of dhikr or zikr (remembrance). These include the recitation of Qur’an and devotional texts particular to the Sufi order in question, called hizb in the Maghreb, as well as religious poetic chanting, centering on praise and supplication to Allah, praise of the Prophet and rhythmic invocations of God. One or more of the divine names used are: Allah, Hayy, Qayyum or simply Hu (“He”), as well as the testimony of faith and tawhid, “la ilaha illa Allah” (there is no god but God).

Rhythmic recitation of names and chanting of religious poetry are frequently performed together. In conservative Sufi orders no instruments are used, only the daf (frame drum); other orders use a range of instrumentation.

The female Hadra performer of the little famous town of Chauen/ Chafchauen who always had a tradition

of reciting the zikr and playing themselves the instruments. They are very well respected as performers.

See the video clip below.

Here we can see the Muqadma at the Lila or Derdeba, starting the ritual in dancing with a bowl of milk

that will be given to every one present starting with the master and the musicians,

This is a very important pix where there is an interaction between the master- M’aalam Mahmoud Guinea

playing the Gimbri and the moqadma Malika (also his wife) dancing into the trance. They are

both from Essaouira, Morocco. Notice the colors of the saints are all here. I know these people.

Photo courtesy of Olivia Rivet

The Lila Ceremony

Terms

|

It is important to mention that all Sufi brotherhoods use music and dance in their ceremonies. Often a sacrifice of an animal needs to be performed. In every ceremony, everyone will be fed as eating the food of the ceremony is a baraka.

All Sufi brotherhoods in the Maghreb, such as the Quadiriya, the Aissawa, relate their spiritual authority to a saint. The ceremonies begin with reciting the Saint’s written works or Hizb (or spiritual prescriptions). In this way they give themselves the authority to perform the ritual. This article is focusing on the Gnawa or Sidi Blel or Sambali ritual.

The Gnawa ceremony, called lila or derdeba is performed all night long. Usually it takes place inside a house or in a zawiya. The first part is mundane, often a kind of procession when the musicians and the M’allem arrive playing music. The music ensemble consists of the M’allem (a lead musician and Sufi master) who plays the guembri (a three string bass) and many musicians who play the T’bol (a bass drum) and the Karkabou (metallic castanets). All musicians are also dancers, as dance is not separated from music.

The Gnawa perform a complex liturgy (lila, derdeba) that recreates the first sacrifice of the genesis of the universe by the evocation of the seven main manifestations of the Divine, the seven saints and the seven mluk or djins (supernatural entities), represented by the seven colors. Therefore the lila ceremony includes seven sections, representing seven saints or ancestral spirits or djinns or Mluk. Each section is associated with a particular color representing the male and female elements or spirits (mixed colors – Sidi Bouderbal, white, green – all saints, red – Sidi Hamou, black – Aicha Kandisha, yellow – Lalla Mira) and each color symbolizes a particular function in nature and beyond.

The mluk are evoked by the seven musical patterns, seven melodic and rhythmic cells (Um) which are repeated and varied, set up the seven suites that form the repertoire of dance and music of the Gnawa ritual. During these seven suites are burned seven different incense and veils or shawls of seven different colors are used to cover the dancers. Each of the seven mluk is accompanied by many characters (mluk or Djins) recognized by the music and by the footsteps of the dance. These entities are treated like “presence” (Hadra) that the consciousness meets in the altered state of consciousness (Hal), are related with mental complexes, human characters or behaviors. Some of the most known spirits amongst the Gnawa group are: Lalla Mira, Lalla Aicha, and Sidi Mimoun are usually related to places like rivers or seas.

The Gnawa’s traditions and beliefs go through a process of cultural assimilation of the new spirit beliefs that originated from animistic pre-Islamic beliefs.

In her article, “Spirits in Morocco”, Anas Farrah explains that,

“In the Islamic tradition the spirits or “ginns” are creatures that lived in earth before the creation of humans, they are also judged based on their actions and some of them will be sent to heaven, others to hell. The Islamic beliefs reinforce the belief of Moroccans in spirits in two other ways directly driven from the Coran texts; the first one is that the spirits or “ginns” are created from fire and the second one is that they burned by comets when they try to reach heaven”(Farrah, page 4)

The aim of the ritual is to reintegrate and to balance the main powers of the human body, made by the same energy that supports the divine creative energy.

The ceremony is performed through a well-established ritual. Fundamental in the ceremony are: the sacrifice of a sheep or a goat, bringing cloths of different colors, eating dates and drinking milk, the burning of incense, playing music and the chant in call and response as well as the dance. Some participants go into a trance where the spirit may come through responding to a typical rhythm or a color. The Derdeba is animated by the M’aalem (the master) and the Moqadma also called Shawwafa (a medium) who is in charge of the accessories and clothing necessary for the ritual. The M’aalam, using his spiritual instrument, the Guembri, calls the saints and the mluk to intorduce them in order to take possession of the followers, who devote themselves to the trance.

This video from the 1980s is performed by the Moroccan Guembri player Paco, with his song, he is calling

a spirit “Baba Hamou” to come for help and bring healing. Here we can see women getting into trance,

some of them standing others already sitting letting their hair loose. I believe this is a video clip as there

are here only women dancing, normally men and women dance together and I don’t see the Muqadma who

takes care of the people getting into trance. There is only at the end a man who bring the orange flower holder.

This video is with the master M’alem Bakbou ( he used to be the bass player and guembri player of the

Moroccan music band Jil Jillala) I met him in London when he was doing a recording and I interpreted for

him. He stayed in my home and we became friend. He is from Marrakech. Here we see the beginning of the

real lila, first the musicians dance and stamp on the ground to call the spirits of the Earth, then people get

fed. After that the bass drums are played and the young girls are holding the candles and some the incense

who are given to the instruments and musicians. The 2 Muqadmaat/mediums enter the courtyard. The

musicians dance. In the dark of the night the Muqadma starts the dance and get into the trance bringing

the messages of the spirits.The colors of the spirits of the dead are used ( black, bue, red, green). The comes

the spirit of the color yellow, the spirit of rthe sun and the sky, called Mira, where everybody dances, it is the

return to Life.

This is a video in English language about the Gnawa festival of Essaouira, Morocco.

The Mluk (sing. Melk) are abstract entities that gather a number of djinn. In the Maghreb, people avoid to call them Djinn. Djinns are known as the “invisible” people. People call them different names in the Maghreb, such as doûk en nâs (these people), Nâs el okrin (the other people), Rjâl Allah or Aït Rebbi (God’s people), mouâl al Ardh (the master of the ground), Rjâl al khafiya (the hidden people) or rouhaniyin (the spirits).

Each Gnawa group gets together with a moqadma, the priestess that leads the trance (Jedba) after feeding the instruments and the various colors brought by her in a bundle with incense. When she gets into a trance, she starts channeling a spirit and may give messages to the community. The Lila ceremony then continues where everyone is dancing until the goal is achieved and the trance is over when the participants have been cleansed from their affliction. The participants negotiate their relationship with the mluk either by placating them if they have been offended or strengthening an existing relationship. Each melk is accompanied by its specific color, incense, rhythm and dance.

In the Maghreb, people do not talk about trance; they just find themselves doing it and it is part of their upbringing, culture and spirituality. Stories about the Mluk were part of any other kind of story. People are aware of their presence and are careful not to harm them. All the tales and stories are based on them and people will avoid their names and places where they might be located. As far as the trance is concerned, it is not limited to a zawiya or to the ceremony such as the Derdeba. People, mostly women, are very sensitive to drums or one kind of music. It is common in the Maghreb that a woman gets into a trance in a wedding or in a concert. People are aware of that and they will take care of that person as she is bringing the baraka to everyone in falling into trance, this shows how Maghrebi people are sensitive to energies.

Furthermore, the French writer Demerghem in “le Culte des Saint” (1954) gives a complete picture of the Sufi Brotherhoods and their rituals in Algeria as he watched them for many years. Not surprisingly, the rituals did not change and the people are still worshiping the saints and their followers. Despite the development of orthodox medicine, people call the Sufi brotherhoods for help.

During the dark years of the Algerian civil war in the 1990’s, women visited each other and played drums, sang and danced until they fell into and trance in order to heal themselves from the stress and sadness. They went back home relieved from their worries and pains.

The picture is showing a young couple where the young woman is playing the gimbri, an instrument that

was supposed to be played only by men, and the young man is playing the karkabou castanet,

This is the picture of the future where both genders are involved in performing side by side.

Bibliography

- Ibrahim Boye,Sayyidi Andal Qadr Djilani, Publisud, Paris 1990

- E. Demerghem, Le Culte des Saints, Gallimard, Paris 1954

- Mohammed Ennaji, Soldats, Domestiques et Comcubines. L’esclavage au Maroc au XIXe siecle, Casablanca: Editions Eddif, 1994

- Viviana Pâques, Religion des esclaves: Recherche de la Confrerie marocaine des Gnawa, Bergamo Italy, Moretti & Vitali, 1991

- U. Topper, Sufis und Heilige im Maghreb, Diederichs Gelbe Reihe, Muenchen 1994

Resources: