From Wikipedia

Sir Donald McCullin, CBE, Hon FRPS (born 9 October 1935), is a British photojournalist, particularly recognized for his war photography and images of urban strife. His career, which began in 1959, has specialised in examining the underside of society, and his photographs have depicted the unemployed, downtrodden and the impoverished.

A master at work: Sir Don McCullin in Kolkata

Film director Clive Booth, cinematographer Chris Clarke and Sir Don McCullin’s manager, Mark George, tell the behind-the-scenes story of how they made the documentary film, McCullin in Kolkata.

Don McCullin has been filmed discussing his photography many times during his long career, but rarely has he been shown shooting in the field. So when plans were mooted for making a documentary showing him in action, with the world’s most renowned photojournalist keen on the concept, they knew they had a rare opportunity that would make the photographic world sit up and take note. The questions was, where did Don want to turn his lens…

Dangerous territory

“We initially planned to film Don in Lebanon, but ISIS moved into the area and it was too dangerous,” says Mark. “We considered filming him photographing Roman buildings in Turkey, but his name has been made shooting people, so we really needed to show him doing that.

“Then Don said, ‘If you want people, we should go to Kolkata. It’s the most unbelievable city in the world.’ When Don tells you that, you know you’re on safe ground.”

While Mark, also the film’s producer, made all the necessary preparations for the shoot to take place, Clive brought award-winning director of photography Chris Clarke on board. They would also be joined by Don’s assistant, Roger Richards, and sound recordist Sean Smith.

Prior to heading for Kolkata, Don was recorded in a studio in Soho, London. This would be used for the voiceover, and allowed the team to plan the film’s narrative.

Rich landscape

Finally, in Spring 2017, after months of meetings and preparation, the team travelled to Kolkata in West Bengal, India. Don had visited the city before and had put forward ideas for locations, but it was agreed there wouldn’t be a pre-arranged storyboard for the shoot.

“We were going to an environment that was rich in imagery for Don, and us too,” says Clive. “He had chosen several places to shoot over a three- or four-day period, and it was really about putting him in that situation and enabling him to do his thing without us being intrusive. This was the key to making it work. Then we would cut the film from what we shot.”

We wanted to replicate Don’s approach to photojournalism.

While Don photographed Kolkata with a Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Chris and Clive – who was acting as a second cameraman, as well as directing – used Canon C300 Mark IIs to film Don. They opted to use EF zoom lenses, predominantly the 16-35mm f/2.8 and the 24-70mm f/2.8, and shot everything using natural light – almost always with the cameras hand-held.

“We wanted to replicate Don’s approach to photojournalism. He has two cameras and two lenses and that’s it – off he goes,” says Chris. “We wanted to keep that kind of ethos. In practical terms we had to be quick on our toes, because of the fast pace of where we were shooting. These environments were either really cramped, or places that were quite open but crowded with thousands of people.”

Intense environment

Filming was done in intense periods of work during the early morning, then Don and the crew would have a break around the middle of the day. This was partly because of the fierce heat and humidity, and partly due to the harsh sunlight at that time. However, it was apparent to Clive that his shooting methods were bearing fruit.

“I could see straight away that our approach was working,” he says. “On the first day, we did a shoot at the market in the morning, then in the afternoon we were thrown into a chaotic environment where Don was photographing in the middle of all this traffic. Health and safety went out of the window. At the end of it, Chris and I agreed it was the most exciting day’s shooting we’d ever had in our careers.”

He was like a caged animal in the car, champing at the bit to get started.

The whole crew were shocked by the extraordinary energy and endurance of the 82-year-old Don. “The years just disappeared and his reactions were phenomenally quick,” says Clive. “He was like a caged animal in the car, champing at the bit to get started. Something would catch his eye and he would say, ‘Stop, stop, stop! We’ve got to get this,’ and he’d be off. Don is always looking, the radar’s on the whole time.”

Chris agrees. “When he sees an image appear in front of him, he has to stop conversation in mid-sentence to shoot it. He’s so passionate about what he’s doing. He’s not just out there trying to find a great composition – that’s really the by-product of his fascination with people. Watching him work was incredible.”

The shoot lived up to the crew and Don’s expectations, but it wasn’t until they returned that the political undercurrents that threatened the shoot were revealed to the team. On trying to hire lighting equipment, Mark discovered it would be very expensive and required employing 18 local people on the shoot. “They said, ‘If you don’t employ us, we’ll find out where you’re shooting, beat you up and take all your cameras and equipment. Don’t think the police will help – we own the police.’” Realising he was dealing with organised criminals – a kind of Indian mafia – Mark moved to minimise the risk. “I struck a deal with them in the end and said I’d employ five of them. They didn’t turn up, except on the last day, when all 18 appeared. They all had broken noses and cauliflower ears – you wouldn’t have wanted to mess with them!”

We’ll find out where you’re shooting, beat you up and take all your cameras and equipment.

Long-distance editing

The team returned from Kolkata with more than 15 hours of footage. The process of editing the film took around three weeks and was done by Clive and his editor, Tristram Edwards. They became the first people in the world to use a new ‘hosted collaboration service’, Adobe Team Projects. Working via Adobe Creative Cloud, Clive, in his Derbyshire home, was able to see Tristram’s screen in London. Tristram would upload the cuts and they could both view and work on them simultaneously.

The resulting 19-minute film is an insightful and revealing portrait of a master of photography in action, in an environment that really pushed him to the limit. This is less about the resulting images, and more about witnessing how Don has successfully captured some of the world’s most celebrated images. “The film’s unique element is that it shows how he does his stuff and you can see his tradecraft,” says Chris. “It’s not just about how he takes pictures technically, but how he conducts himself with people in difficult situations – things that are so interesting to watch him do.”

For Clive, it’s been an all-consuming project and he’s delighted with the outcome. “There’s no single aspect of the film I’m not immensely proud of,” he says. “That includes the subject matter, the cinematography, the music and the editing. It’s really about showing Don in a way that most people won’t have seen him before and I’m grateful to Canon for giving us the room to do it as we wanted. For me, hand on heart, it’s the best piece of work I’ve ever done.”

McCullin in Kolkata was premiered at Camerimage 2017, in Poland. To find out more about the latest EOS 5D camera, the EOS 5D Mark IV, which McCullin used in India, visit the product page.

Written by

THE PLATINUM PRINTROOM

![]()

Exhibition Catalogue Introduction

I was lucky enough to meet photographer Don McCullin and artist/photographer Paul Caffell of 31 Studio around the same time in the late 1980s when I was the curator of the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) Collection, then located in Bath, and worked with both of them on exhibitions in the 1990s.

Both Paul and Don often viewed the 19th century photographs in the RPS Collection; McCullin loved the deep rich tonal range and subject matter of Roger Fenton’s and Francis Frith’s gold-toned albumen prints, whilst Paul repeatedly looked at every one of the several hundred platinum prints in the collection, over the years.

By that time, McCullin was no longer photographing war and conflict, the displacement and privation of peoples for which he is so well known and respected but concentrating on rather more peaceful, serene and contemplative subjects – his annual visits to India, local Somerset landscapes and a series of still lifes. He characteristically printed his “fist-like” (his phrase) black and white prints very forcefully with strong tonal contrasts, sleeping badly the night before printing. I suggested to him that some of his non-war material would look quite beautiful printed by the platinum/palladium process which, with its infinite tonal range, had the ability to draw out and emphasise subtle detail. In the 1990s Paul Caffell’s 31 Studio had completely mastered the complexities of late 19th/early 20th century platinum printing and were producing exquisite prints of their own work, limited editions for photographers including Sebastãio Salgado, David Bailey, Linda McCartney and others. They also created portfolios from the negatives of acknowledged early 20th century platinum masters like Frederick H Evans and Alvin Langdon Coburn.

Platinum is ideally suited to McCullin’s brooding landscapes and scudding skies and to the reflective surfaces, light patterns and intrinsic detail in his still lifes but it especially performs a wonderful alchemy on the skin tones of his many African and Asian portraits, enabling them to both absorb and reflect light.

McCullin, who is extremely protective of his negatives, and fastidious about their safety and handling, was finally convinced to work with 31 Studio by Sebastião Salgado, whose long-term Genesis project the Studio has now been printing for several years.

So twenty years after that first suggestion, here* are Don McCullin’s amazing images, chosen by himself and printed in platinum by Paul, his son Max and Dominic Burd.

They are worth every minute of the wait.

Pamela Glasson Roberts

Former curator of The Royal Photographic Society

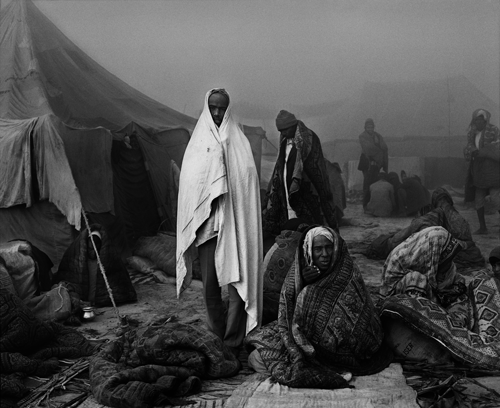

Early Morning at the Kumbha Mela, Allahabad, India 1989 – © Don McCullin

Don McCullin | Platinum Prints

* The Subscription Rooms, Stroud, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom – November 2012

An exhibition of 31 Studio’s Platinum Prints, curated by Fred Chance and Carlos Ordonez of PhotoStroud in 2012.

Click on Navigation to the left to view the exhibition images

Don McCullin interview: ‘I take more than I bring. That’s not a role I’m proud of’

Jenny McCartney talks to the celebrated photojournalist about war, guilt and Aylan

The thing that the photojournalist Don McCullin likes best of all now, he tells me, is to stand on Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland in a blizzard. He made his name in conflicts in Vietnam, Cambodia, Biafra, Uganda — hot places full of fury, panic and death — but these days he finds his greatest solace in the English landscape. I can see why he is drawn to that wild part of Britain: its isolated beauty, the feeling of being roughed up by the elements but not destroyed by them. Clean air, too: you must get a cool, fresh lungful up there.

He’s 80 years old in October: talking to him at home in Somerset, I get the sense he’s been coming up for air all his life. There wasn’t much oxygen, either physically or intellectually, where he grew up, in a damp, two-room tenement home in London’s Finsbury Park. His father, a gentle man, was permanently invalided with chronic asthma exacerbated by the coal-fire smog of the era: ‘He couldn’t walk very far or breathe very well.’ He loved his father dearly — ‘he meant the world to me’ — and his death, when McCullin was 14, was a crushing blow. ‘It made me aggressive,’ he says. ‘I said, “I’m going to give up God.”’

He was left with his two younger siblings and his mother, a fiery, strong woman who was often primed for a scrap. ‘When she gave you a clout you knew what time of day it was.’ Was he close to her? ‘Too close. I found her oppressive, really.’ His dyslexia made learning difficult, and he used to play truant and go and hunt for grass snakes and birds’ eggs at the end of the Piccadilly line. He went to work on the railways at 15 to support his family.

He’s not nostalgic for post-war Finsbury Park, with its fug of ‘bigotry and ignorance …I always felt as if somebody was treading on my windpipe.’ Still, it gave him some ineradicable qualities. Toughness, certainly: on foreign assignments McCullin held his nerve in circumstances of unimaginable stress. It also taught him what he didn’t like: bullies, in and out of uniform.

It was Finsbury Park, too, that gave him his first big break, when his photograph of the street gang that he used to hang out with, the Guvnors, was accepted by the Observer. The picture hangs in his most recent exhibition, at Hamiltons Gallery in Mayfair. It is blown up big, the better to show its precocious sense of structure. The boys, elegantly boxed in the ruins of a bombed-out building, model delinquency in their Sunday suits: they had been caught up in a fight with a rival gang in which a policeman had been killed. The day after it was published, offers of work began flooding in.

When you look at the other photographs — the ones McCullin took in war zones — what still astonishes is not simply the fact that these pictures exist, ripped from the thick of the action, but also the sureness of their composition: the shellshocked US marine in the Battle of Hue in Vietnam, his haunted face perfectly symmetrical; the female Christian Phalange fighter sinuously pitching a grenade, framed by concrete and steel.

McCullin came to loathe the cruelty of war, even while the rush of it became addictive. How did it feel to be around people such as the Phalange, as they unleashed their frenzied massacres against Palestinians in Beirut? A look comes over his face like ice glazing a pond. ‘You despise their jokes and their bestial attitude to people.’ He hit a rough patch at 52, he says. ‘I didn’t go to the Falklands and that broke my spirit. Then my wife died.’ He left the Sunday Times when Rupert Murdoch took over, and human suffering was deemed old hat. It still infuriates him.

His job put bread on the table, but it must have been hard on Christine, his first wife of 22 years, negotiating domestic life alone with three children. ‘There’s something selfish about career,’ he says. ‘I always felt I had priority, but it’s obnoxious to think like that really.’ She died of a brain tumour at 48: a tragedy complicated by guilt, as McCullin still loved her but had left her for another woman. He says, ‘It was a bit of a cheek really, her life being stolen so quickly.’ I have noticed that he uses understatement for the memories that wound the most.

McCullin doesn’t think of himself as a writer, although he says he has enjoyed the company of some of the best: the novelist Chinua Achebe, James Fox, Bruce Chatwin. But he has the writer’s instinct for a phrase that can cut you to the quick. He describes the little albino boy in Biafra who crept up and took hold of his hand, one of 800 children he found dying in a makeshift orphanage in 1969. ‘You don’t think that was easy for me to look at that starving albino boy who had licked out the inside of this French corn-beef tin and made it look like a brand new Rolls-Royce. I know where I’m coming from; I know what I bring and what I take. I take more than I bring; I bring hope but I give nothing. That’s not the role I’m proud of.’

All McCullin had to give the boy was a barley sugar sweet. The memory still shocks and haunts him. ‘I haven’t printed his picture for years in my darkroom. It’s a terrible thing to be alone in the darkroom with that boy, as if he’s coming back. He wouldn’t have lasted for more than a few days after I took that picture.’ When he could help, he did: there’s a picture taken by another photographer of McCullin in Cyprus in 1964, carrying an elderly lady away from the fighting.

Age has landed unpredictable punches on him. It went for his heart — he had a quadruple bypass five years ago — but pretty much left his face alone. He looks much younger than his years, his cheeks almost unlined, light blue eyes quick, the mind hungry for fodder. Despite the accolades, he hasn’t drifted towards self-importance: he’s often very funny, a sharp mimic, a bit cheeky. His passion is for landscapes now, but he still has the twitchy reflexes of a news guy, alert to what Louis MacNeice meant when he wrote that the ‘world is crazier and more of it than we think’. Next up is a trip to Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan.

News sometimes seems to follow his footsteps: for his book Southern Frontiers in 2010, about Roman ruins, he took some beautiful, brooding black-and-white photographs of the temples at the historic site of Palmyra, now occupied and partially destroyed by Islamic State. ‘I absolutely fell in love with it. I met the director who was sadly beheaded, a wonderful man.’

Does he believe in the afterlife? ‘No I don’t. I believe that’s it. You go into the ether and that’s it.’ He sorely misses his friend and travelling companion, the conservationist Mark Shand, who died in New York last year: ‘I loved him.’ When he himself dies, he says, he wants to be cremated and scattered down by the river in the valley near his house. But for now, he says, ‘The barometer of joy is going up. Up and up.’ Why now? I ask. ‘Well, because of her really.’ He means Catherine Fairweather, his third wife, with whom he has a plainly beloved 13-year-old son, Max.

He drives me to the station and we pull up as the train is already at the platform. ‘You’ll have to hurry!’ he says, and I belt for it. I don’t think, then, about his past — full of the juddering promise of planes, close shaves and second chances — but I can see that, even in this sleepy Somerset station, something about just making it by the skin of your teeth has exhilarated him. When he suddenly reappears to shake my hand at the window just before the train moves off, he is beaming, his face lit up like a boy’s.

Don McCullin: Eighty is at Hamiltons Gallery until 3 October.