Hinterland definitions :

- a region lying inland from a coast

- a region remote from urban areas, a region lying beyond major metropolitan or cultural centers

West Penwith is a region in the far west of the United Kingdom.

The region is surrounded by ocean, so does not meet the first of the above definitions, but the coastline is wild and ferocious and is a natural barrier to serious travel. As the most westerly region of the UK it wholly meets the second consideration.

The following rolling blog post and photographs depict something of its characteristics, focussing centrally on its historical mining perspective, but also exploring other landscape associations and philosophical notions which may provide a more comprehensive and inclusive assessment of the region.

It is also an exercise in assisting me to understand more cogently the nature of ‘landscape’.

21.12.2024

These photographs were taken on winter Solstice, in firstly St Just and later at the site of Wheal Owles at the end of Truthwall Lane. They again mostly focus on the actual and cultural ubiquity of iconic mining engine houses, but also the substance, the materiality, of the landscap . It rained virtually all day; the wind in the afternoon was 50-60 mph on the cliffs and moorland. The photographs do not try to change the reality of anything and simply portray a stormy day in the West Penwith landscape.

Several months ago I pondered how to photographically depict historical objects, times and landscapes. One way I’ve now considered is to focus on detail, the minutae and micro-structures of a landscape. On this peninsula the granite stone informs everything, the lichen is possibly the oldest living thing in the environment, the grasses are swept by the same winds that blew 150 years ago, ivy still fastens a tenacious holding onto monuments, the paths are the same paths that were walked upon by ancestors. The relationships between things in the landscape remain fundamentally the same; depicting the relationships between objects may suggest either previous or even future relationships, behaviours which exist before may recur again.

The diffusion caused by using a wide aperture, the selective focus on single objects within a landscape, the spatial cliff edges where distance or foreground fades into tone all contribute to an illusion we maybe viewing a claustrophobic vista of relentless matter which at some point becomes landless and timeless.

19.12.2024

A sunny day in West Penwith, the landscape changes.

18.12.2024

Vignettes from around the St Just area.

17.12.2024

Graffiti found beside an old tiny harbour at the extreme end of Newlyn on the path towards Mousehole. There is a frequent reference to ‘Yew Boy’ who I assume is the artist. There are occasional derogatory references ( maybe to others or perhaps self-condemnatory ? ) and a condemnation of ‘2nd home owners’ in the region. I can find no information on Yew Boy.

16.11.2024

Pendeen Churchyard

15.11.2024

St Just and Geevor Tin Mine Landscape

14.11.2024

Botallack

17.10.2024

Wheal Owles, Wheal Owles West and Wheal Drea and the journeys between over 3 days.

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

10.09.2024

This entry and its included photographs are also a separate blog post in its own right found here. The words and images are an important part of this reflective journey through the West Penwith mining landscape, and developing some further understanding of landscape being existential; ie being multi-layered with multiple meanings. There are also multiple participants in experiencing/deciphering the images I have created; myself with the original exploration and selection of micro-landscapes to photograph, and those viewing the images. Where does any ‘phenomenology’ come into being; with me as the photographer ( which I believe to be true ) or with those who are viewing and creating their own internal associations? What is that relationship?

Also I have recently introduced the notion of a ‘palimpsest’, a living tapestry of layers which reveals all of those layers despite new information being added. Can a town, or a region, and its many stratas be regarded as a palimpsest?

Blog Post

I have recently considered the idea that the landscape around us is multi-factorial and multi-dimensional. A landscape may be viewed as a collection of layers of occupation where marks left by successive communities are similar in conceptual terms to those marks left by painters on a canvas. The only variable is the perceptual and selective preferences chosen by each person passing through that landscape; that landscape will be critically different for everyone who passes through.

Over the past few days I have spent time in West Penwith, west Cornwall, during the time of its annual Lafrowda Festival. The Festival’s stated aims are :

- To advance education in art and culture in particular, but not exclusively, in the St Just in Penwith area.

- To promote arts for the benefit of the public generally, and in particular for the inhabitants of St Just in Penwith, by promoting an annual festival of arts and music

This year’s theme was ‘Going Underground’ and a range of activities and performances were organised to reflect this theme.

The town and surrounding area is most well known for its mining and Wesleyan Heritage. It maybe difficult to entirely separate them over the last two hundred years. What is left of the mining environment has been formally declared a World Heritage Site and is now protected. Cornish miners and mining engineers are also celebrated for taking their skills and knowledge around the world, assisting with the development of mining industries in many countries. An important part of that ‘diaspora’ has been the strong following of Christian faith; both the Church of England and the Methodist Church has played important roles. The accumulated temporal, spiritual and industrial layers of all of these events provide a living tapestry upon which St Just continues to shine its unique star.

These photographs provide a snapshot of how, on those few days over the rain and mist at Lafrowda Festival, I saw those complex and subtly resonating layers of local landscape.

09.09.2024

Hannah Bennett died in 1881, and her children had a memorial drinking fountain placed on Chyandour Cliff, Penzance, in 1886. The fountain overlooks Mounts Bay on the busy road into Penzance. Chyandour stream issues into the Bay on the left and Penzance train station is on the right. The distant Lizard peninsula can just be seen on the horizon.

However what relevance does this fountain have to photographing a mining community? It feels strongly to me it does have relevance and, apart from the obvious date-congruence, there feels something more. The date association provides an envelop for further development, however just accepting the date relationship feels coldly insufficient. I feel a desire to develop a more comprehensive idea of who Hannah actually was, and how her life actually manifested, a construction which entails something both warmer and empathic than merely considering a random date. That comprehension relies upon both imagination and other factors, but what are those other factors which provide a real relationship between Hannah as a living and breathing person and an era of mining which is well detailed in history books?

03.09.2024

On Penzance sea front, left of the Western-most railway station in Great Britain and looking out over Mount’s Bay, is a sea defence system in the form of a long curling concrete wave. Graffiti has been drawn along its entire length. Just to its left is the cliff at Chyandour and just beyond the cliff, and the old Bolitho estate offices where the Chyandour stream chuckles into that Bay, the great tin smelting plant stood for some 250 years, its large 4 chimneyed workplace now a coal yard.

In an English county which begat Alfred Wallis and a modernist movement, not much appears to have changed in terms of artistic sentiment. Looking at the ‘tags’ of the graffiti, the intellectual might plaintively scream ‘but what of the narrative? and traditionalists might not have noticed that the world has welcomed the ubiquity of street art into its national and international galleries. Others might celebrate that the voices of minorities have a canvas too. At its most socially and artistically reductive it is worthless graffiti, to others it signifies more.

A palimpsest is a document which provides layer upon layer of visual information without essentially occluding older detail; it is a testimony to different eras, time frames, opinions, cultural associations and even religious convictions captured in one expressive form. It is a living document which may continue to develop as a part of an evolutionary process, detailing something more immersive than a static present.

These continue my interest in street art, or even street semiotics. I wonder how many people have contributed to these works, over what kind of period, and who those people were, where they live and what their lives consist of? In a mining area, they beguilingly remind me of tin mines, where layers of human activity and endeavour and thought created something, dug down deep into a firmament of some kind. They are Breton’s surrealism and Höch’s collage. They inter-act with the sea, buffer with nature, blister in the sun and wrestle with the politics of our post-truth world.

The street art on the concrete wave at Penzance and the nearby tinners’ cliffs can be considered palimpsests, another word for the accretion of multi-layered industrial and cultural typography as described by Schama.

30.08.2024

Photographs from 6th August incorporate a full day of photographic activity. Images from the children’s play park at Pendeen overlook both the sea and the ‘head gear’ of Victory shaft at Geevor Mine, a liminal and historic environment where children are born into and grow and develop within a living and breathing Cornish diaspora. Photographs from the cliffs of Botallack portray the proximity of the Count House ( now a National Trust cafe ) and rentable accommodation where a large pool once provided water for the ore ‘dressing floors’ lower down the cliffs.

The twin pump engine houses of the Crowns mines at sea level and a further 2 above, constructed approximately 1858, were once sufficiently famous to attract Prince and Princess of Wales ( later Edward v11 and Queen Alexandra ) to visit in 1865. In addition to the vertical shafts driven down into the cliffs and spreading like horizontal roots of a tree both out to sea and under land almost as far as St Just, a steam powered tramway on an incline of 32 degrees was constructed. Following the royal visit, the subterranean tramway became famous with wealthy tourists, who were charged a £1 to take the ride into the mine. Its official use was to negate the need for the exhausting and time consuming use of ladders, and ‘cages’ took miners 1000 feet down into the depths for working their shifts, and also brought the ore to the surface. In April 1863 the chain which hauled the ‘skips’ up and down snapped, and 8 miners were killed as their ore-laden skip hurtled downwards out of control.

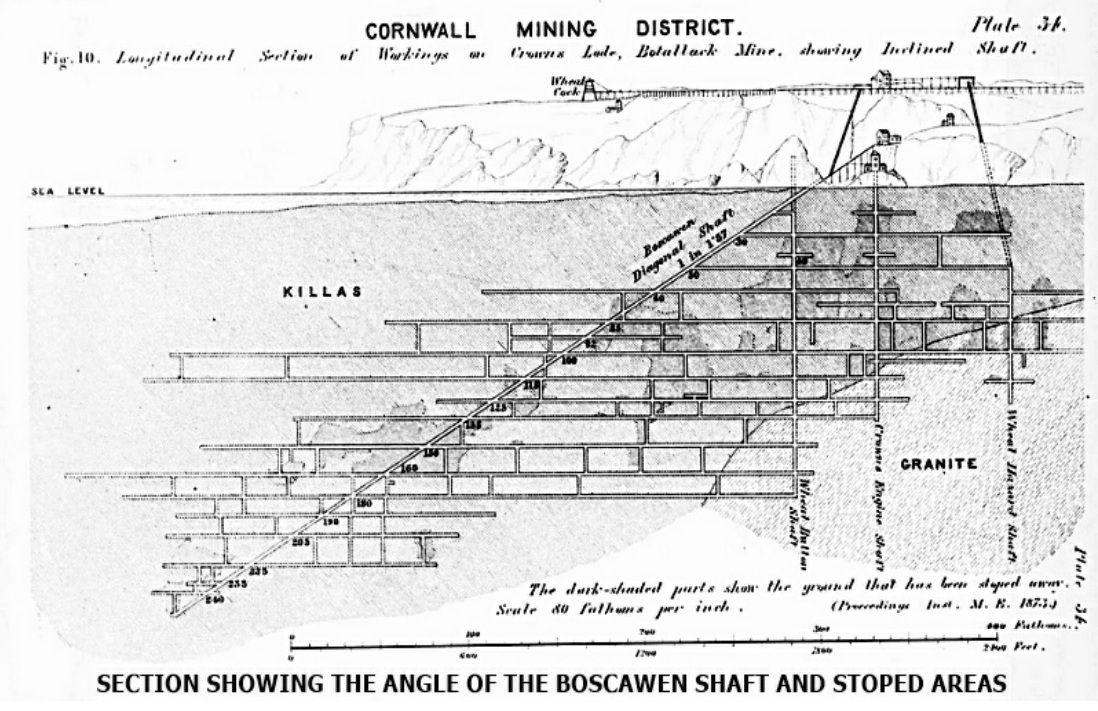

Diagram from https://nmrs.org.uk/mines-map/metal/cornwall-devon-mines/st-just-area/botallack/botallack/

The final images portray the pump engine house of West Wheal Owles mine. This mine, also known by its original name of Cardogna shaft, experienced an even greater tragedy in January 1893 when a shaft was inadvertently flooded by waters from Wheal Drea, an adjacent mine, and 20 miners lost their lives, their bodies never recovered. The mine’s majority owner and purser Richard Boynes was later held responsible for not allowing the variation of magnetic north in his planning and blasting calculations and was fined £15 in Penzance magistrate court for his negligence. It was said that Boynes never recovered from this devastating event.

The West Wheal Owles engine house was portrayed as Wheal Leisure in the most recent Poldark series some 5 years ago. The original Wheal Owles mine, Wheal Drea and the house Boynes lived in at the time, I discovered only in the last few days of this most recent trip.

I ask myself how to associate with this landscape, this history and this diaspora, a collection of dimensions I have been walking through regularly for a number of months now. How can photography, or my mind via the medium of photography, understand and experience it more fully? It has taken me several months for the layers of meta-culture to be sufficiently absorbed into me so that I feel at last some connection with this small region in west Cornwall, enough at least to begin to work with.

It also interests me how that absorption and immersion occurs; the balance and relationship between intellectually understanding a region and actually experiencing it.

There is much repetition in the series of images I have taken, and the same landscape although remaining objectively static can subjectively differ according to weather, light and the photographer’s own changing internal landscape; developing rapport and relationship with a landscape by increasing familiarity with it deepens that assimilation and helps to accommodate wider variation and interpretation of those experiences. Also I wonder how can the landscape of history be effectively navigated, the many people, families and traditions which went before, the landscape of faith which was pre-eminent here? What marks remain and where to look?

It reminds me of the important archaeological concept of materiality ( the abiding evidence in any shape or form of previous occupation and existence in any landscape ) I was exposed to in Spain and on Orkney, and also the meta-physical notion of phenomenology, of being utterly in the moment and open to one’s own innate anamnesis, or instinctual collective memory, as described by archaeologist

Alfredo González-Ruibal in my article here.

Is ‘landscape’, rather than a topographical concept, cumulatively everything we physically encounter, everything we bring with us as sentient individuals, everything traditionally and culturally locally embedded within the dimension we travel through and everything we both sense and imagine and visualise as we forage for sensation and maybe images? If so that landscape is vast and boundless and boundaried only by our own intrinsic personal and intellectual make-ups, and by our own curiosity and risk taking. We can personally experience that landscape totally in a wide-vista horizon to horizon perception, or in the fluttering of a leaf, or a solid single rock, or a drop of water. Who is to say whether our individual experience of landscape is adequate, sensitive or complete?

A series of images of the Botallack Count House environs, now a National Trust cafe and holiday let, is below. The cafe here, managed by staff from Geevor Mine, is marvellous for coffee and cake. It is also the venue of a monthly folk club meeting and is famous within Cornwall for its association with Cornish bard and folk singer Brenda Wootten.

The cafe overlooks the remains of the Botallack mine sett; Botallack Mine, Wheal Cock, The Arsenic Works, West Wheal Owles and Wheal Edward dominate the coastal landscape here.

Although worked manually as a mine before, the first steam engine was installed in approximately 1800 at Carnyorth Moor

Wikipedia tells us that :

The following shafts were working in 1884,

- Botallack engine-shaft, 220 fathoms (1,320 ft; 400 m) deep and worked with a 30 inches (760 mm) cylinder

- Crowns engine-shaft, 130 fathoms (780 ft; 240 m) deep and worked with a 36 inches (910 mm) cylinder

- Wheal Cock engine-shaft, 160 fathoms (960 ft; 290 m) deep and worked with a 30 inches (760 mm) cylinder

- Carnyorth engine-shaft, 130 fathoms (780 ft; 240 m) deep and worked with a 30 inches (760 mm) cylinder

- Wheal Cock skip-shaft, 170 fathoms (1,020 ft; 310 m) deep

- Botallack skip-shaft, 205 fathoms (1,230 ft; 375 m) deep

- Carnyorth skip-shaft, 124 fathoms (744 ft; 227 m) deep

- Wheal Hazzard skip-shaft, 100 fathoms (600 ft; 180 m) deep

- Chy Cornish skip-shaft, 100 fathoms (600 ft; 180 m) deep

- Pearce’s skip-shaft, 130 fathoms (780 ft; 240 m) deep

- Bullion skip-shaft, 185 fathoms (1,110 ft; 338 m) deep

- Durloe skip-shaft, 70 fathoms (420 ft; 130 m) deep

- Rodd’s skip-shaft, 60 fathoms (360 ft; 110 m) deep

- Boscawen diagonal-shaft, about 500 fathoms (3,000 ft; 910 m) long, perpendicular depth 240 fathoms (1,440 ft; 440 m) and 300 fathoms (1,800 ft; 550 m) under the sea

- Approximately 10 other shafts varying in depth from a few fathoms to 50 fathoms (300 ft; 91 m) deep.[7]

A total of 265 workers were employed and the monthly wage was approximately £800 per month. The average monthly yield of the mine was about 19 tons of tin, 3 tons of copper and 4 tons of arsenic. The mine closed in 1895 as a result of falling tin and copper prices.

Some considered it the centre or the hub of the mining industry in West Penwith.

A series of images below portray the famous Crowns mines almost at sea level at Botallack. It was here the incline began its descent into the sub-ocean rock at 32 degrees.

Wikipedia suggests :

There are two engine houses and the remains of another pair on the cliff slopes above; the mine extends for about 400 metres out under the Atlantic ocean; the deepest shaft is 250 fathoms (about 500 metres) below sea level. The workings of Botallack Mine extend inland as far as the St Just to St Ives road, and at times included Wheal Cock further to the north-east.

The mine buildings on Botallack Cliffs are protected by the National Trust. There are two arsenic works opposite the Botallack Mine count house. At the top of the cliffs there is also the remains of one of the mine’s arsenic-refining works.

The mineral Botallackite has its type locality here.

In my photographs I have chosen to try to present the ruins of the engine houses simply, featuring their physicality and strength and monumentality within their dramatic setting, making no allusion to anything other than their history as robust and stolid architectural tools to mankind, and their ambitious mining owners. The bulk and size of the granite blocks are sculptural in their heft and regularity, but there is no attempt to create a more reflective aesthetic. The taut rusting wire images may symbolise something other, maybe the sliding descent into an industrial linearality of the history of these structures, or a suggestion of the physical sliding act of mine shafts descending. The smoothness of that implied descent is misleading, though the rust and decay suggests a linear process of industrialised aging and change. The two bolts on the wire are entirely intentional.

Below a series of images portray West Wheal Owles mine at Botallack. Portraying something more emotional requires a more reflective and emotive set of visual circumstances. As written above, West Wheal Owles was the site of a tragedy in January 1893 when, whilst continuing to follow a lode, errors in cartography meant that blasting along a rich lode of ore created a fissure into an entirely different shaft and mine which had been abandoned and flooded in 1884. The implosion of water was so prodigious that a giant roar presaged a mighty wind which blew out all the candles, plunged the mine into darkness and panic and precipated a torrent of water which rapidly filled 95 fathoms ( or 570 vertical feet) of mineshafts in 30 minutes. Of the 40 miners working underground on that morning, 20 perished, their bodies never recovered.

A comprehensive analysis of the events, including a list of those miners killed, and an account of the litigation process in Penzance and judgement against Richard Boynes, the mine’s majority owner and purser, can be found

here

Cornish poet W. Herbert Thomas recalls the events in a poem titled The Flooding of Wheal Owles published in 1893.

Tellee about Wheal Owles, sir—the flooded Cornish mine!

’Ow the waters chuck’d the levels where the sun don’t never shine;

’Ow the twenty men are lyin’—stark, lifeless, lumps of clay,

Where the rushin’ torrent wash’d thum when the rock-wall brawk away.

Tellee about the blastin’, and the frantic climb to “grass”? (a)

Iss, sure. I’ll try to tellee ’ow the whole thing cum to pass;

Tho’ you knaw I aren’t a schollard, cause my school was Wheal Owles bal, (b)

An ’my pen was a three poun’ hammer, an’ my books some stones to spal.

Ef you look across the valley, past the crafts an’ hedges there,

You can see the ’count-house standin’ top the hillside brown an’ bare,

An’ the shaft es by the cliff, sir, where the restless ocean rolls,

An’ under the sea some levels was drove from old Wheal Owles.

Ef you went down at Botallack, or Levant p’r’aps you’ve heard tell

’Ow above your head the boulders would haive with the billows’ swell;

An’ you’d hear them gratin’, runblin’, ’bove the forty-fathom end,

An’ you’d clemb the ladders quicker than you managed to descend.

But I’m mixin’ up my story, as I fear’d I shud ’ave done,

For my head is mizzy maazy fer sence this whistness(d) ’ave begun,

An’ you wudden feel quite fitty(e) ef you met Death faace to faace,

An’ weth roarin’ drownin’ waters you ’ad a fearful chaase’

Aw, sir, I caan’t set quiet, fur the gasldy thing do stir

Every drop of blood within me, an’ I’ll tellee plainly, sir,

Tho’ they said my nerve was steady an’ head level through et all,

I dream of a Hell of water, which in thunderin’ floods do fall:

It happen’d a Tuesday mornen, this awful accident,

We were all ave us forenoon core, sir, an’ w’en from home I went

I took my crowst(f) from the missus an’ gov her a parten kiss,

An’ we knaw’d no more than the dead, sir, ’ow things wud ’ave gone amiss.

I wus haaf way down the valley w’en I found I’d come away

Thouse(g) my under-groun’ clothes—for Monday, at St. Just, es washin’ day:

So I started back in a hurry, an’ got to the cottage-door,

An’ said ef I stay’d more’n a minute I’d be late for the forenoon core.

My under-groun’ suit was ready, but my wife looked fine un queer;

An’ I says, “W’y wass the matter!” and says she, “I’ve took a fear,

For you knaw tes allus unlucky to come back when goin’ to work,”

An’ she looked as white as a witch, sir, an’ cold as that blacken’d churk.

It gave me a bit of a twingle, but I laugh’d to aise her mind,

An’ I aren’t so superstitious as some men you may find,

But the fear come back, she told me, as soon as I was gone,

An’ the fearful thing that happen’d was worse than she thought upon.

At the bal we met the cappen—I main Cappen Tom Tregear—

As straight a man as a mother cud ever have an’ rear,

An’ we got our strings ave candles an’ fuse an’ dynamite,

For to blast the ground down under, an’ to have a bit of light.

Then we all clemb’d down the ladders, about forty men, all told,

An’ up through the shaft to daylight we sung, an’ the sound uproll’d,

For we had some brae fine (h) singers from the Bible Christian choir,

An’ we like to tuney below, sir, or around a blacksmith’s fire.

We sung “In the sweet by-an-bye,” sir, ’bout the beautiful golden shore,

Where we hope we shall some day gather, an’ never to part any more;

But we never thought Death was waitin’ to beckon us over the tide,

An’ that mornen haaf ave our number wud cross to the other side!

So we clembed to the lower levels of the damp an’ slimy ground

Where the candles smoked an’ sputtered, an’ the tin an’ copper es found;

An’ we went to the stopes an’ winzes an’ ends where the lode ave ore

Es blasted an’ rulled in the waggons by miners every core.

I’ad shut one hole an’ was usin’ the hammer an’ pickers there,

When a sound like ten thousand thunders broke out through the heated air,

An’ I heard the rush an’ the roarin’, like the burstin’ of a tide,

An’ “Water! The mine is flooded! Run for your lives!” I cried.

My comrades were stunned with the horror, an’ I might ’ave stood there too,

Like a lump of lead or a statue, an’ not knaw’d what to do,

But I well remember’d the floodin’ of the next bal, old Wheal Drea,

When the water of East Boscean broke through an’ wash’d me away.

As quick as a flash of lightnin’ I hurried the men an’ boys

Into the empty waggon; an’, urged on by the noise

Of the roarin’, risin’ water that swamped the works below,

I pushed the load through the level so fast as my legs would go.

One lad fell out of the waggon, down eighteen feet to a plot

But Jim bent down as he clemb’d up, an’ the boy’s hand quickly caught,

An’ hualed(j) him up so aisy, did that fear’d excited man,

As ef but a pound of candles, or awnly a onion stran.

Then on to the shaft we rumbled, while a lad who run’d before

Shriek’d lest the waggon should crush him, as it onward madly tore,

An’ dodgin’ the rocks out-juttin’ by one candle that kept alight

In the rush of the wind, we managed to reach the shaft all right.

Up through the shaft came wailin’ the cries of the drownin’ men,

Strugglin’ in darkness with torrents that roll’d down again an’ again,

Till the gashly an’ helpless bodies sunk down like lifeless stones,

An’ the roar of the hungry water swallowed their dyin’ groans.

By the skin of their teeth some escaped, sir, by climben chains hand over hand,

An’ some, who took the wrong turning, near went to the sperrit land,

Some were haaled up by the winches, an’ some who fell off the way

Were helped again on to the ladders or would not be living to-day.

Down below is a rever of water, a mile an’ half long, for sure,

Through three mines’ deep under-ground workin’s, an’ p’r’aps a good many more,

For a pare(k) of our men was drivin an’ cut into old Wheal Drea,

Where the thousand-tons water was pressin’, an’ burst through Cargodna that day.

A blunder? Ah yes, ’twas a blunder, for our plans shawed solid ground

Where the men at the sixty-five level a hollowed-out place must have found:

You see, sir, they worked for metals in our bals in days of old,

When Solomon decked out es Temple with tin an’ with jewels an’ gold;

So we’re hedged in with scals(l) of dangers, an’ tes little enough we get

To keep body and soul together, but we aren’t the sort to fret

W’en we come up to the sunlight an’ can in our homes abide,

But ’tes hard when homes are waitin’ for bodies beneath the tide.

So that es the awful story of the floodin’ of Wheal Owles,

Thas ’ow the blinds are lowered an’ the Church-bell sadly tolls;

The mine is now a grave-yard, an’ the levels are the graves,

An’ the miners’ dust there slumbers near the wild Atlantic waves!

https://west-penwith.org.uk/owles2.htm

The following photographs of West Wheal Owles pump engine house were taken at dusk. The Cornish cliffs overlooking the Atlantic and under the quickly changing skies contain their own energies and beauty.

Of course, these opinions, thoughts and words are only wholly relevant today; comprehension is ephemeral and developmental, tomorrow my understanding and interpretation will be slightly different, and this landscape will have metamorphasised into a different imago. When is a painting, novel or any creative endeavour, or even a human being, ever fully actualised?

24.08.2024

I am continuing the West Penwith series with a gallery of images photographed on 5th August at Botallack. The time was approaching 7pm and as evening transitioned into the beginning of night, mist and cloud was obscuring much of the distant landscape and compressing tonally and subjectively the immediate landscape. I wondered whether the images would hold up in colour but even as I began making photographs felt internally they might better suit a monochrome presentation.

I have rendered the images as dark as I dare, intentionally trying to evoke a more emotional rendition and commentary on the dark nature of mining which lies behind a common presumption of romanticism and nostalgia. The more I read of the mining heritage the more I can move beyond the prettiness of colour and sunscapes and into another diaspora.

Simon Schama’s words, whilst describing Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, began to take a literal form potentially attributable to West Penwith ‘ the rod of commercial penetration that ends in disorientation, dementia, and death, was an ancient obsession’ and ‘even the landscapes that we suppose to be most free of our culture may turn out, on closer inspection, to be its product.‘

15.08.2024

As I continue with this project, I need to understand more the notion of ‘Landscape’. What is it? How can it be understood? Is ‘landscape’ merely the physical ground which surrounds us at any one time, areas we choose to walk in and out of as we please?

Some quotes from Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory regarding the nature of Landscape

Page 5. : For it seemed that the idea of the Thames as a line of time as well as space was itself a shared tradition.

Had I reached back further into the literature of river argosies, I would have discovered that Conrad’s imperial stream, the rod of commercial penetration that ends in disorientation, dementia, and death, was an ancient obsession

To go upstream was, I knew, to go backward : from the metropolitan din to ancient silence; westward toward the source of the waters, the beginning of Britain in the Celtic limestone.

Page 6. : And if a child’s vision of nature can already be loaded with complicating memories, myths and meanings, how much more elaborately wrought is that through which our adult eyes survey the landscape. For although we are accustomed to separate nature and human perception into two realms, they are, in fact, indivisible. Before it can ever be a repose for the senses, landscape is the work of the mind. Its scenery is built up from as much from memory as from layers of rock.

Page 7 : ….And it is this irreversibly modified world, from the polar caps to the equatorial forests, that is all the nature we have.

Page 7 : ( Regarding Yosemite Natural Park ) The wilderness, after all, does not locate itself, does not name itself…….Nor could the wilderness venerate itself……It needed.hallowing visitations from New England preachers…., photographers…..painters….., and painters in prose…. To represent it as the holy park of the West.

Page 9. : Ansel Adams …..did his best to to translate his reverence into spectacular nature icons……. Explained that ….. He photographed Yosemite in the way he did to sanctify a ‘religious idea’, and ‘to inquire of my own soul just what the primeval scene really signifies…..’In the last analysis….Half Dome is just a piece of rock….There is some deep personal distillation of spirit and concept which moulds these earthly facts into some transcendental emotional and spiritual experience……unfortunately, in order to keep it pure we have to occupy it.’

Even the landscapes that we suppose to be most free of our culture may turn out, on closer inspection, to be its product.

And it is the argument of Landscape and Memory that that this is not a cause for guilt and sorrow but of celebration……So while we acknowledge ( as we must ) that the impact of humanity of the earth’s ecology has not been an unmixed blessing, neither has the relationship between nature and culture been an unrelieved and predetermined calamity

At the very least it seems right to acknowledge that it is our shaping perception that makes the difference between raw matter and landscape.

05.08.2024

Porthnanven ( also kown locally as Cot Valley ) is a former mining location where mines and industrial buildings lined both sides of the valley and its stream leading out from St Just down to the sea. Some evidence of that heritage remains in the form of walls and foundations though most of it has been removed. Some mine shafts are still dangerously accessible and adits lead out onto the beach and can be entered. It is now mostly famous for its unusual beach, strewn with large oval rocks which have dropped down from a hanging beach just behind the shoreline.

The morning was overcast when I took these photographs, there was little colour. My ambition was to capture the sculptural qualities of the granite…. More visits are required.

04.08.2024

Images late in the day, depicting mostly the mines of Higher Bal and Lavant. It may be the ruins of the mine workings which engender most interest but I think in terms of cultural and imaginative appeal they are the most limiting; photographs of them are ‘easy hits’. Finding more subtle appreciations of the landscape and local culture is the real challenge though these iconic locations remain difficult to ignore.

Images depicting Pendeen church, churchyard and the path leading up to the carn and quarry where granite was obtained by miners for the construction of the church in 1851.

Images depicting churchyards in St Just in Penwith

03.08.2024

After a rainy night camping in Pendeen, the weather was brighter in the morning. I stayed at the North Inn, an old miner’s pub in the centre of Pendeen, and decided to walk around the village and cross over the fields to Geevor Mine, then walk along the cliffs to Botallack and return to Pendeen. These are the photographs below. I always enjoy meeting and chatting with local people and a man I met said that ‘Geevor’ translated to ‘Goats tin stream’ in Cornish. The original tin gathering accured in and around streams. Geevor mine dominates Pendeen, and its main Victory shaft and buildings can be seen all around. There are frequent references to mining everywhere, house names, old mining buildings used for other purposes or converted into homes, and many visual references mostly the insignia of the engine house.

The first image is of a model of a miner and a mining cart filled with flowers. This is from thecar park of the North Inn pub, where I was staying, and provides unambiguous notice of its mining heritage. The last image is of the Count House in Pendeen, a building where miners bid for the lodes they wished to mine and then received their reward from Mine Captains and owners. I was erroneously advised that a steam tramway took ore from the mines to the smelting works at Chyandour, Penzance, in fact the transportation appears to been have across the moor by mule and horses until the advent of the internal combustion engine.

The photogreaph of the map is from Botallack Natural Trust cafe and a depiction of the levels of the Crowns mines found at the bottom of the cliffs.

02.08.2024

The following photographs are of a deserted and deteriorated Wesleyan Chapel on the moor road from Penzance to St Just, in the village of Newbridge. The double crucifix’s beside the road have long attracted my interest and the chapel itself looks rundown and becoming derelict. The little churchyard adjacent to it looks reasonably well tended and contains some interesting artifacts. A traditional glass memorial ornament was on one grave, with the glass smashed and the metal frame rusting, and on the grave of man with the Biblical christian name of Ephraim who had died over 100 years ago, was a full bottle of both Proper Job and Hicks beer.

Leaving the cemetery, the gate looks across the Penzance to the St Just road and then across the moor. It is close to a location where tracks diverted away from this main carriageway to take ore away from the mines on the north coast for smelting to the Chyandour plant at Penzance, and to deliver mail and passengers to Pendeen from Penzance by horse and cart. I have yet to find these old routes.

I later arrived at Pendeen, where I camped at the North Inn pub. I visited the miners’ built Pendeen Church as the light was fading.

Some photographs obtained walking around St Just in Penwith

13.07.2024

Photographs from 17th June 2024. As I walked from Kenidjack along the cliffs to Botallack, where my car was parked, the sunset was remarkable. It lent a romantic and fantastical character to the cliff landscape and the ruined engine houses, guaranteed to detract from an objective depiction.

Some photographs from 16th June 2024, mostly of the closed Geevor Tin Mine, but also of the cliffs overlooking Porthnanven and Carn Gloose ( Ballowal Barrow ). One image is monochrome.

The first gallery is taken with a Nikon D810 camera and the second gallery with a Fuji GFX50r camera.

Nikon D810

Fuji GFX 50r

Below are a collection of photographs taken on 18th June at Geevor and its ruined buildings overlooking the Atlantic ocean. I photographed into the night which led to extended exposure times and unusual colours. The images are portrayed in both colour and monochrome but contain the same images; the two sets evoke different cognitive and emotional responses.

These photographs, taken in January 2024, depict the landscape of the small fishing cove of Porthgwarra and the buildings and associated topography of several farms I passed on my return to the B3315 at the small hamlet of Polgigga. It was a very misty day, which partially cleared at sea level at Porthgwarra, but as I climbed back inland the mists returned and the very traditional farm buildings of Roskestal quickly became enveloped in mist. Although not considered a mining locality, Porthgwarra is situated very closely to the traditional mining landscape of West Penwith, and its use of granite for buildings and the mists and agriculture I encountered are all very representative of the region.

24.01.2024

These photographs depict a post-Christmas St Just, though the mist and the cloud remain impenetrable over the community.

Whilst in St Just I listened to a radio show presented by the BBC film critic Mark Kermode where he and a fellow presenter reviewed movies which had referenced dream sequences as a major part of its narrative and discussed directors who had purposefully used dreams to impart symbolism and ambiguity. Alfred Hitchcock, Luis Bunuel, David Lynch, Ingmar Bergman and Pedro Almodóvar are some of these directors, several of whom integrated the visual landscape of Salador Dali. Reality becomes displaced, distortion prevails and often surrealism, Freudian and Jungian semiotics predominate.

The mist over St Just may contribute to a similar experience within that landscape. Mist reduces contrast and dilutes colour; it compresses experience rather than expands it, and distorts and alters reality. Mist contributes to a brooding, obsessional experience, of a landscape constrained both by the physical limitations imposed by weather and by our own imagination.

These photographs were taken either inside or in close proximity to the churchyard of St Just Parish Church.

23.12.2023

Here is a selection of photographs taken from 20th to the 24th of December 2023 between the town of St Just in Penwith and the hamlet of Morvah. On each of those days a bank of cloud hung over the region, and a cold, strong wind blew in from off the Atlantic ocean. The photographs are deliberately presented as darker to better match the conditions.

These photographs are the most recent images in a continuing photographic depiction of the region, focussing mostly on the tin mining heritage found here and partly portray a Community readying itself for Christmas.

Related