The clue to a fine monochrome negative is to give so much exposure as to give rich detail in the shadows, and so little development as to avoid highlights becoming too dense to print with subtle graduation. The vast majority of the negatives arriving in the Fine Print Photographers Workshop have been underexposed and overdeveloped making a fine print an impossibility This applies to amateur and professional, novice or expert, using ultra modern sophisticated cameras or old fashioned basic cameras.

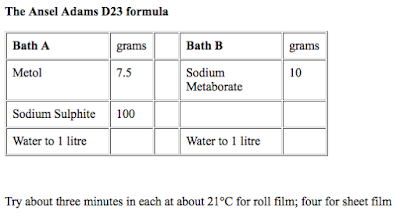

Actually, it is less common with people using simple older cameras. Two bath development is far from new. Heinrich Stoëckler recommended a formula before the second world war that was popular with Leica users, and it still works really well today. Ansel Adams did not invent, but used and publicised a different formula based on Kodak D23 that also worked well, especially for larger format negatives of high contrast subjects. It is hard to understand why the process is not more widely used.

There are a couple of proprietary versions. The American Diafine is very well proven in its speed enhancing properties, but is not widely available in the U.K. Tetenal make Emofin which also increases the speed of some films, but rather defeats one of the great benefits of two baths by requiring different times for different films.

The formulae given below allow one to process different makes and speeds of film together for very similar times, and you can use the same at a pinch and still get acceptable negs. They are not fussy about time and temperature within reasonable limits, they have outstanding capacity, they keep well, they are sharp and fine grained, and they are very low cost. All of these factors make two bath development attractive anyway, but they miss the main benefit.

If you use sheet film, and are a careful worker, you can expose and develop each sheet individually by zone system procedures to produce the best negative possible to allow production of fine prints. If you use roll film, unless you very carefully group all pictures of the same subject brightness range on to the same roll, you cannot give appropriate development to each exposure and some compromise development has to be given to the whole roll.

If the subject brightness range for each picture is low, this isn’t too much of a problem since the latitude of the film will normally allows a good quality, if not fine, print to be made. If, though, the subject brightness range exceeds the films range (and it often does) or exactly matches it, then there is no latitude even if the exposure is exactly right with the use of a precisely calibrated spot meter. If a cameras automatic meter is used, then it is highly likely that the exposure varies from the ideal no matter how sophisticated it is supposed to be, especially if the effective film speed has not been ascertained by personal test.

What two bath development does is to try and compensate for these variables in each individual negative automatically to produce full toned negatives that print more easily for high quality. This means that a negative of a low contrast subject continues to develop up to produce a good printing contrast, while, more importantly, negatives of high contrast subjects have the highlights held back while the shadows continue to be built up so that detail can be printed easily at both ends of the scale. All this happens automatically for different films developed together for the same time.

The technique is the same for all versions of the two bath. Bath A contains only the developing agents and preservative and sometimes a restrainer. Bath B contains the accelerator, and sometimes a restrainer. The film is developed in Bath A with agitation every half or full minute -its not critical. Actually little development takes place. Mostly the film is becoming saturated with the developing solution.

However, some development does take place and agitation is important to prevent streaking. The solution is then poured off and saved. Drain the tank well but don’t rinse or use a stop bath. Then pour in Bath B, and after a quick rap of the tank on a hard surface to dislodge any air bells, let the tank stand still with no agitation for three minutes or so when all development has ceased. Note, though, that while no agitation is ideal, and usually works well for unsprocketed roll film (120/220), there can be streamers from 35mm sprocket holes. This seems to vary with different kinds of tanks, different films, and the local water characteristics. Do your own experiments to determine the minimum agitation you can achieve without streaking before committing a crucial film to the process. Perhaps try one minute intervals to start with.

In the second bath the developer soaked into the film emulsion is activated by the accelerator. In the highlight regions where the developed silver will be densest, the developer available in the emulsion is soon exhausted and development halts, thus automatically limiting the density of the negative at that point.

The more the exposure, and the denser the highlight, the faster development ceases. In the shadows, though, there is little silver to reduce and there is enough developer to keep working there to push up the shadow detail density. The less light the negative received at this point the longer the development proceeds. Indeed there is a minor hump put into the characteristic curve of many films between the shadow and mid tones to give heightened shadow contrast. The effect is not the same as the well known technique of compensating development by diluting developers, which does work in holding back dense highlights, but can give muddy mid times and does not have the same automatic contrast equalisation as the two bath.

Of course there is a limit to the contrast that can be equalised, but most negatives will print to good quality on 2 or 3 grades of paper with only the most extreme contrast range subjects requiring other contrast control methods for printing. For the very economical chemicals and scales one source is Rayco at 199 King Street, Hoyland, Barnsley S74 9LJ.

The Stoëckler formula is very soft working and gives very fine grain. With today’s thin emulsion films which do not soak up as much of either Bath A or Bath B, thus resulting in less development activity, it can be too soft. Beware, too, of the second baths very mild alkalis losing effectiveness. You may need to refresh it with extra borax from time to time. You do not need special photographic chemical grade for this. The anhydrous type freely available from High Street pharmacists will be fine.

The Ansel Adams formula is quite “robust”, and you should beware too high a contrast on roll film cut times if necessary. My own formula is somewhere in between for contrast, has extra acutance, and does not suffer the second bath exhaustion to which the Stoëckler mix is prone. You should get at least 15 roll films through my formula, and more if you then refresh the second bath with more sodium metaborate.

THE TEASPOONFUL TWO-BATH

As far as I know nobody has mentioned another technique which I have evolved and which works really well to give different tonal characteristics and very similar automatic contrast control, and to avoid having to mix anything but an approximate Bath B two heaped teaspoons of sodium metaborate in 1 litre of water.

It dissolves almost instantly and is cheap enough to use once then throw away, though it would handle 15 roll films if re-used. Simply use your normal standard developer (T-Max, ID11, llfotech, HC110, Econotol, Perceptol etc.) for half to two thirds of the makers stated time as Bath A, drain it off, and use the teaspoon-measured Bath B for 3 minutes at the same temperature as Bath A.

You may have to fine tune Bath A time by experience. For all 2 baths stop and fix afterwards in the usual way after Bath B, but not between the two baths.

OLD – THE ORIGINAL STÖECKLER TWO BATH

While the use of two bath developers goes back into the mists of photographic time, one man deserves the credit for bringing the wonderful advantages of the process to the mass of photographers – Heinrich Stöecker. He had already devised a very successful rapid acting two bath developer back in the 1930s for press use. As the Leica made 35mm a force to be reckoned with, he turned his attention to that format.

In the 30s, films were still thick emulsion, and 35mm photographers fought a battle with grain. Stöeckler’s two bath for 35mm was published in Leica News and Technique pre-war. It was an instant hit among the Leicaphiles and other 35mm enthusiasts. It was a very simple formula which treated the grainy emulsions with absolute kid gloves. It gave VERY soft working for minimum grain and maximum compensation, essential with the emulsions of the time if highlight exposures were not to be pushed over the shoulder of the characteristic curve during development and thus block up.

The automatic delicate graduation was also very valuable to these first users of long rolls of film with very variable subject brightness range shots. Previously, photographers using plates or sheet film could adjust exposure and development for each individual image. The Stöeckler two bath also became very popular with architectural photographers for building interiors, such as churches, where there is a huge subject brightness range when exterior windows appear along with shadowed interiors.

With today’s thin emulsion films, the formula is often too soft working, and there is often a speed loss of about 2/3 stop. However, it does give a certain smooth ‘look’ which many photographers find very appealing – with child and female portraits for instance – and architectural photographers still find it a wonderful developer. FP4 loves it! Available direct from Fine Print with history and very detailed instructions in an A+B, *1.5* litre each, pack.

Please note that developers have occasionally been sold under this name (well, actually, the name has been misspelled) where the formula has been altered for ease of manufacture and distribution. This sometimes resulted in crystallisation and settling out of the second bath. The developer we sell is the correct original formula and has none of these problems.

OLD! THE ORIGINAL BEUTLER DEVELOPER

After the war, the first thin emulsion films began to emerge, originally from Adox. Leica users, again pushing technique forward, discovered that very slow versions of these films could be used for their fine grain. However, they tended to be very contrasty, and a compensating developer was needed to tame this.

At the same time it was discovered that the acutance could be stepped up to give very high definition in these films with enhanced edge effects with specially designed developers. The king of these developers was the formula introduced by Willi Beutler which reduced the amount of developing agent and increasing the alkalinity of the accelerator. This gave very high edge effects indeed and controlled overall contrast simultaneously.

An added advantage was that film speed with these slow emulsions was increased – usually by about half a stop. Because the developing agent and alkali activator are stored separately, then mixed just before use, the storage life is again very long. All the film and developer manufacturers soon made thin emulsion slow films and similar high definition developers.

Over the years, film grain size in medium and fast films reduced, and the need for the ultra slow films receded. However, the introduction of special grain films like T-Max 100 and Delta 100, gave the same fine grain as the previous ultra slow films, but they also gave some of the same problems in sudden drop-out of shadows, for instance, as the previous contrasty slow films.

Many non-special grain films too evolved to have ‘straight line’ characteristic curves where shadow drop-out could easily occur with automatic exposure cameras in contrasty lighting conditions. The special grain films had ultra-fine grain and resolution, but their apparent sharpness sometimes did not match that of high acutance traditional thin emulsion films.

Suddenly, the Beutler formula made sense again. Just try it with T-Max 100 for instance to see what it can do for crisp definition, full utilisation of film speed and easy printability. Available direct from Fine Print with very detailed instructions in an A+B, *1.5 litre* each, pack.

FINDING YOUR REAL PERSONAL FILM SPEED

At my Fine Print Photographer’s Workshop I often get requests to process film and make prints from photographers who have uprated their film speed. Occasionally this is fully justified: in situations such as available light interiors, where no picture would have been possible without a film speed increase, or to achieve a deliberately stark effect.

Usually though the photographer has uprated for no apparent reason, as though there were some points to be won by doing so. It’s almost macho to uprate. They even do it when it makes matters more difficult in taking – when there is glaring sun and an EI 1600 film speed leaves the camera without suitable shutter speed and aperture combinations.

I am sure film manufacturers are very aware of the sales appeal of high film speeds. There are few extra sales in claiming that your film is slower than everybody else’s, but probably quite a few if it is claimed to be high speed and ultra fine grain as well. To be fair, some major steps have been made in the last decade thanks to new grain technology. Some ISO 400 films do now have the grain of the old 125 emulsions, and new 100 emulsions better the grain of older ultra-slow types.

What is more to the point is whether any of those figures are valid in practise anyway. I, and many other more expert photographers, have found that makers’ speed ratings don’t stand up in practise, and far from being uprated, they should be downrated. Typically, standard ISO 400 emulsions work out at about 160, and 125 at 50 or 64 (I exclude T-Max from this).

Sceptical readers are probably right now saying, “Oh yeah” So why do I say this? I mentioned earlier that exposure meters are set to read any scene as if it were ‘average’ or ‘middle’ grey: the standard 18% reflectance which manufacturers like Kodak reproduce in their commonly available grey card. I have a question. Who says that the average of a typical scene is 18% grey? Nobody I have asked has been able to tell me how this assumption arose. If it is incorrect, then we immediately have an error effectively in the nominal film speed. I believe the correct ‘middle grey’ should, in fact, be more like 9%.

There is much confusion about this ‘average’ or ‘middle’ terminology as well. When asked, many of my clients say they visualise it as the exact mid-point between black and white; the reading given by a meter pointed at, say, a chessboard with an exactly equal number of equally sized black and white squares. In fact, such a scene would give a reading, theoretically, of exactly half the reflected light of a totally white board. Half the light means the same as one stop less or one zone less; so, if pure white is zone X, then the chess board would indicate zone 1X on the meter, not the stipulated zone V for middle grey. To get a zone V reading, the chessboard would have to have around 80% of its area black.

Try it with a mock up and you will see this is so. But is this 18% right anyway? If the luminance range of a typical photographic scene is around seven stops – and a surprisingly large proportion do seem to be – then that is 2.1 in log terms. Half of this is 1.05, which translates to a reflectance value of around 9%. (If you’re not into sensitometry, take my word for it!) Nevertheless exposure meters are supposedly set to render anything they read as standard 18% grey, which is zone V in the zone system.

Since zone 0 is solid black, then we can work out what should happen at each zone if the maker’s speed is as claimed. By then running a very simple test, we can check if the claim is right on our own equipment (in a way that will eliminate all questions about what is real middle grey) and if it isn’t what the correct speed is for us. Makers set film speeds in a laboratory using laboratory instruments. We work in real life with ordinary instruments, cameras, enlargers, etc. For instance, have you ever checked your meter?

I have two different spot meters, a Pentax and a Soligor. The Pentax reads 2/3 stop faster than the Soligor at low levels and 1/2 stop faster at high levels. My Weston and various camera meters all give different readings from the same subject under the same light, but vary differently at different light levels. Similarly, the llford digital thermometer I use is 1’C adrift from my Kodak mercury version. When all the other possible variables in taking and processing, such as shutter speeds, real lens light transmission compared to marked aperture, flare factors, lens extension, agitation technique etc, are taken into account it’s not surprising that practice deviates from laboratory theory.

Theoretically it’s possible that all the factors could pull in one direction to give a higher than nominal speed. But I have never come across it in hundreds of cases. It is also true that some film makers have stopped quoting rigid ISO speeds in favour of an EI (exposure index) figure. The basis for this isn’t always clear, but Kodak’s own publications state that a four stop subject brightness range for full detail in shadow and highlight is considered normal. If the scene you are picturing exceeds this, and almost any landscape with sky will, then the film speed will be too high to record details in the shadows as well as the highlights.

In describing how to determine your true film speed, Kodak actually say that most people generally find they need a number slightly lower than the film’s rated speed (Kodak Workshop Series, Advanced Black-and-White Photography). They discuss one hypothetical test, which set a photographer’s personal system film speed for T-Max 100 at 50. There is nothing wrong with this and it does not imply that Kodak films are slower than others. Indeed, my own experience is that T-Max films are more accurately rated than most.

Kodak are to be congratulated for their clarity in the criteria they use. It is fortunate that it is simple and instructive to find your own true personal film speed. It is far harder to describe than to carry out. Zone 0, printing as paper maximum black, or as near as practically makes no difference, means an area in the negative that has received so little light during exposure that it is simply the clear base of the film plus any inevitable fog from development – not surprisingly known as the ‘film base plus fog’ density. Note that this is not nil exposure – it takes a certain degree of exposure before anything begins to show on the film after development. Once this point – the inertia point – is passed, density begins to build up on the film as exposure to light increases.

There comes a point where enough density occurs after development that it will just visibly register when printed on paper. In other words, if you find the shortest possible printing exposure at which a negative of film base plus fog density produces paper maximum black when processed, and then use the identical exposure and print processing for the second slightly more dense negative, then we would just be able to see that the tone produced was not maximum black but a discernibly different very dark grey. This is how zone 1 is described: the deepest possible grey discernible from black, and it is theoretically set at a negative density value of 0.1 above film base plus fog.

This is easily measured with a densitometer, but a simple practical test with our own equipment is probably more accurate and useful. Since each zone above zone 1 is achieved by doubling the exposure (i.e. increasing by one stop), we can move back down from the meter indicated exposure for zone V in the same way to reach the theoretically correct exposure to produce zone l for the claimed film speed.

If the speed is right, it will produce a just ‘unblack’ grey when printed identically with a zone 0 film base plus fog negative from the same film. If the claimed film speed is too fast, it will print as black, and if it is too slow, it will print as too light a grey. The test procedure is simple and often a revelation. Set the camera up outside in even, unchanging light (not always easy – try a north- facing wall on a bright, overcast day).

Don’t use flash or artificial light, they are unreliable for these tests. To avoid lens extension, keep the camera focused on infinity and fi11 the frame with an even-toned target – it could be a plain concrete wall or a piece of grey coloured card, though not a bright colour because meter cells vary in colour sensitivity.

Remember, don’t focus. Meter the surface in your usual way, taking care not to let your own shadow influence the reading and to meter as closely as you can to the lens axis. Use a middling manual shutter speed because these tend to be more accurate. Set the indicated exposure – this is set for theoretical zone V.

Try to get an aperture and shutter speed combination that will allow you to stop down five stops without changing shutter speed and also avoiding full aperture. Don’t worry about the speed too much, but do avoid full aperture. Now close down four stops and the exposure will be at theoretical zone 1. So if zone V was 1/15 at f/4, stop the aperture down to f/16 to reach zone 1. Make an exposure at this setting, which ought to be correct, but probably won’t be. To find out if it is the correct zone 1, we shoot some more frames bracketed in as small aperture increments as possible. This might be approximate half stops by setting the aperture. ring between click stops or you may be lucky in having 1/3 stop click settings, or maybe you can override your shutter speeds (in manual, not auto) by 1/3 stops.

Make careful notes of the exposure for each frame. Now cap the lens and shoot off two or three frames to produce some zone 0 totally unexposed negatives. Use the rest of the roll on any old pictures – we just need to avoid processing with lots of blank frames, which might affect relative developer activity.

Obviously sheet film users just shoot the precise number of frames they need, including a zone 0. Now develop in your normal developer. Development time has little effect on low zone areas compared to high, but it does have some, and we are working very close to the lower limit here. So contrary to normal textbook advice to use the developer manufacturer’s recommended development time for your film, I ask you to develop for 20% less time for reasons that become very clear later.

Use an absolutely standardised development routine for equipment, temperature, agitation, pre-wet, etc. Be meticulous – it makes you feel good! Set up your enlarger at around a medium-sized enlargement and focus accurately using any suitable negative. Replace the focusing negative with a film base plus fog zone 0 frame from the test shots and stop the lens down two or three stops, as convenient for subsequent length of print exposure.

Use freshly mixed supplies of your preferred regular processing solutions at precise temperatures, and your normal paper. If graded, use grade 2; if variable contrast, use the exact middle grade of 2.5. Using one second increments, or smaller if you can control them accurately, make a test strip of the zone 0 frame such that there are steps of grey across the print reaching full black about half way across the strip.

Develop this in an absolutely standard and repeatable way. I strongly advise you not to standardise on an extended development time. You now need to find the first step on the test strip which reached maximum black, but don’t judge this until the print is dry! The first black strip will be the one which can’t be distinguished from its neighbour. It’s normal for strips that are obviously different when wet to merge when dry – known as the ‘dry-down’ effect. Once this minimum exposure time for maximum black has been established, you simply substitute each of the theoretically correct and bracketed zone 1 negatives in turn, making no other changes to the enlarger settings or processing procedure.

Give each of these negatives exactly the same exposure time as the minimum required to produce maximum black on the zone 0 negative. This is the source of another common error, both in this test and in making print exposures after test strips normally. Having made the test strip in a series of intermittent short exposures, the subsequent print is mistakenly made with one long composite exposure.

For example, if the test strip showed correct exposure at seven one-second exposures, the print is then made with one seven-second exposure. Due to what is known as ‘the intermittency effect’, this is wrong. The single longer exposure will produce significantly greater density than several intermittent ones of the same total duration. Even many professional printers are unaware of this and attribute the difference to dry-down, which is present as well. So make your actual prints exactly as the test strip, in exactly the same multiple intermittent exposures.

Mark the original camera exposure on the back of each print as it is made. When they are dry compare them with the maximum black print, and find the print which shows the first change away from black. This is zone 1 for you, and only for this equipment and technique. Theoretically, if you change anything, you should retest. In practise, it’s not critical unless you’re a fanatical purist.

However, it’s wise now and then to retest anyway with negatives tagged on to a normal film – materials and techniques gradually change and drift. I have never yet known a film speed that a zone 1 test did not discover to be lower than the maker’s rating. The amount of variance will show by how much you had to ‘overexpose’ marked on the back of the relevant print. For example, if you had to over-expose by one stop to get your zone 1 negative, you need to halve the manufacturer’s recommended rating. Unless you shoot with your own true film speed, you will always have empty black shadows unavoidably.

PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT TIMES

For much the same reason as film speed is personal, so too is the ‘normal’ development time. The right personal time for any developer you use is very simply established. Use exactly the same shooting and processing procedure as you did to find true film speed. Indeed, it is convenient to do it at the same time.

When making exposures of the test target, as well as doing those at zone I, just off black, make some bracketed exposures at zone IX, just off white, by increasing the indicated zone V exposure by four stops. Keep notes of the various exposures. You will probably need two more rolls or sets of sheets with zone IX exposures too, so save time and eliminate variables by making them at the same time.

Process the first film for 20% less than the maker’s stated time, as described for the film speed test. Find the bracketed exposure at zone IX that is the same film speed as the zone I exposure that proved by test to be the real film speed; i.e. if the true zone I negative was one stop slower than the maker’s speed, find the zone IX frame that is also exposed at one stop less than the maker’s speed. Print this frame exactly the same as the zone I frame, i.e. at the same intermittent print exposure and with the same processing.

Logically, this print at zone IX should be a very pale grey barely different from white. To check this, process a piece of unexposed paper in the same way and dry them both before comparison. If there is no difference, the film is overdeveloped, ie the zone IX negative frame has too much density and is printing as zone X (white).

Remember, development has a progressively greater effect the higher up the zone range you go. In this case, you will need to cut development (try a further 10% cut) and repeat the test. On the other hand, if the zone IX print has more than the merest trace of grey tone, the development time was too short causing zone IX to print too dark, and you should extend it by, say, 10% and try the print test again.

Usually with two tests like this you will be so close that you can make a very accurate estimate of the precise development time needed for a zone IX exposure to print as zone IX grey. This estimate can be verified by a further test usually tagged on the end of a film or set of sheets in normal use. . This procedure establishes your normal (‘N’) development time.

I have never known a case where the correct time proved to be more than the maker’s stipulation, and it is often less by 30%. Using the maker’s time will therefore produce negatives with blocked highlights, and the difference in grain is very marked. I still don’t understand why, but the depth of field also seems more with the shorter development – perhaps it’s just an illusion. Sometimes when a subject is metered before taking we realise that the brightly lit areas are measuring above zone IX and will therefore print as paper base white, when we need them to show some tone.

These tones can be ‘pulled in’ to printing range by further reducing development time. The exact reduction is found by repeating the development time test, but this time use a frame exposed five stops over the meter’s indicated zone V reading to achieve zone X. By finding a development time that yields a print of zone IX grey from the zone X frame, we have compressed the scale by one zone. This is known as N-1 development.

To pull in by two zones, retest with a zone XI exposure processed to print as zone IX. This will be your N-2 time. Take care with this amount of compression however. All the zones get compressed and, though proportionately more at the top end, it begins to show badly in the middle tones which can look muddy in the print.

Film speeds will probably also fall a little further, requiring either precise further testing or the usually sufficient rule of thumb addition of an extra half stop exposure. In a low contrast scene where the range of subject brightness falls short of all the zones, the contrast can be expanded to fit.

You can establish the correct amount to increase development times by similar N+1 and N+2 tests. You will often find that the maker’s recommended time is about right for N +1. Again true film speeds may need fine-tuning with around a half stop reduction in exposure, i.e. a 50% increase in film speed from the figure you already ascertained by testing for a normal subject brightness range.

TAKING CONTROL

It is encouraging for newcomers to the use of the zone system of exposure and development control that it very soon operates as an unconscious and rapid process not of setting camera controls, but of seeing the image required in its correct tones of grey. It’s a freeing of vision, not a pedantic technical exercise.

Actually, it is incorrect to talk of a photographer using or not using the zone system. Quite a few ‘serious’ photographers have told me that they don’t choose to get involved in all this technical hang up – their interest is only in taking the picture. To my mind, that’s like chefs with all the ingredients before them saying they can’t be bothered with all this cookery business – “my interest is only in the final meal”.

Usually with photographers it also boils down to “can’t be bothered”. These are often the self same photographers who use that dreadful phrase, “it didn’t come out”. Encouraged by many amateur photographic magazines, they bracket exposures above and below the indicated averaged meter reading. This is not only music to the ears of film manufacturers, it confirms the photographer as a guesser. It relegates the creative process to some form of gambling: if the tonal range in the image is not too wide, one of the exposures may achieve the desired result.

Whether the imagined picture arrives is purely luck of the draw. This is sad because the photographer, in attempting to visualise the end result, is apparently intent on artistic achievement, but is at the same time depriving himself of the surest available means of realising the vision. Let me be clear. I believe a photographer works with the zone system of exposure whether he or she likes it or not, simply because the zones are the immutable laws of densitometry.

It is, quite simply, what happens regardless when an exposure is made. The only questions are: does the particular photographer understand what is happening; does the photographer know how to control it; does the photographer know how far that control extends; and can the photographer pre- visualise the image required and achievable?

If the answer is “no” to any of these questions, then the whole process becomes a lottery with the occasional lucky strike spaced out with the usual massive majority of frustrating failures. Indeed, much of the satisfaction is removed from the odd success because the photographer didn’t really cause it.

So does the use of the zone system guarantee success, if only in terms of a technically good negative? Unfortunately not. We are human and make mistakes. My list of embarrassing failures would rival anyone’s. Though I never say “it didn’t come out”, I guess my expletives at the sight of a nearly black or virtually transparent negative emerging from the fix have grown more picturesque over the years.

All I will say is that whenever 1 have forgotten to allow for a filter factor, forgotten to set the correct film speed on my meter, forgotten to withdraw the dark slide, or failed in many similar ways, it will always have been with a magic but unrepeatable picture, or one that had meant hiking miles over tough terrain to the point of exhaustion.

A JOLLY GOOD TANNING

There’s a second approach to automatically holding back negative highlight densities while shadow densities are nursed up in development to produce fine negatives capable of fine prints. Its tanning. 19th century developers often used Pyrogallic acid as their main agent. This has the property of releasing by-products during development which tan the gelatin in which the film emulsion is held, but of doing this proportionately according to exposure density. Thus in the dense highlights tanning is greater and faster. This inhibits the access of fresh developer solution to the emulsion and the highlight is automatically restrained. It also encourages the formation of edge sharpness effects and inhibits softening of resolution.

Pyro is known, along with Pyroctachin (which also tans) as the highest definition developer of all. It fell into disuse for various reasons. It gained a reputation for instability and inconsistency it went off quickly and was hard to control. It is a hazardous material. It also stained film, hands and anything else with a yellow/green colour. The addition of sodium sulphite cut out the stain and helped to preserve but it was still expensive and less reliable than more recent agents such as Metol, But the stain is actually desirable to knowledgeable photographers. It stains the gelatin between the grain clumps.

The stain colour is non-actinic. This means that it is printing density. So it at least partially “fills-in” the spaces between the grain clumps to smooth out the graininess significantly. Not only that, but the stain is again proportion- ate to the negative density. With variable contrast printing papers the yellow/green stain is the equivalent of a softer contrast filter, but one that is automatically varied according to the negative density. So highlights are automatically even further restrained and hold subtle detail in the print.

With graded paper, the stain provides the opposite extra printing contrast in the highlights. This means that pyro acts like a sort of Multigrade negative developer. If your neg, turns out soft, you can print it on a graded paper to gain extra contrast; if hard, on a variable contrast paper to lose 1 to 2 grades of contrast (depending on film and paper type).

The old bugbears of expense and lack of controllability/longevity have all been overcome with a Pyro formulation known as PMK (Pyro/Metol/Kodalk) which is de- signed to give the greatest stain possible and the utmost definition. It is by Gordon Hutchings of the U.S.A. who has done a fine job of evolving and broadcasting its formula. Handle the Pyro with proper care when mixing following the suppliers safety advice.

Use distilled (not just purified or deionised water). Mix at low temperatures of about 26 degrees. Solution B is saturated and may well take 24 hours to dissolve with an occasional shake up at room temperature even with distilled water. You may even have to heat it a little. The solutions are used diluted one shot, are very economical, and the stock solutions last well over 12 months in well sealed brown glass bottles

For use mix one part of Solution A with two parts of Solution B to 100 parts of water. Most roll film s take about 8 minutes at 2 I °C for graded paper, plus about 20% for V.C. paper.

Solution B is a saturated solution and should be mixed at room temperature. It will take several hours to fully dissolve. If you have trouble dissolving it completely, use twice the amount of water, and mix four parts of solution B with one part of A with 100 parts of water for use.

Remember to save the used developing solution which should be dark brown in colour after use due to the oxidisation that causes the film staining. To achieve the right amount of staining, after the film is fixed, rinse it briefly in plain water, then resoak in the used developer with occasional agitation for 2 minutes.

Discard the developer and wash the film in the usual way for at least 20 minutes when the stain will often further intensify. Stain varies according to the make and type of film. New on the scene is DiXactol, Barry Thorntons own proprietary developer which is the only one to combine two bath development and improved tanning/staining ultra high definition development.

For its tanning/staining and sharpness, HP5 Plus in 120 and sheet is brilliant. Delta 100 and T-Max 100 are great in 35mm. Also in all formats try Fortépan 100 from Silverprint cheap and curly, but great tanning/staining and sharpness. For 127 try Jessops own brand film.

DiXactol can be only be obtained by post from Barry Thornton.

Hands up! Who remembers Fry’s Five Boys Chocolate? You know. The one with the picture of the five expressions on a boy’s face as he anticipated, enjoyed, then reminisced about the pleasure of the chocolate bar. I often see a photographic four face equivalent.

I stand there in front of a new group of keen monochrome photographers. The place is packed. The first audience at the beginning of the day is full of vim and vigour, keen to be out and round the NEC hall for the Focus on Imaging exhibition after this Ilford Masterclass. By the end of the day, for my final class, they come in very glad to be able to rest their weary feet after a day around the hall.

But all audiences, fresh or tired, young or old, North or South, display the same four reactions at the same point fairly early on in the class. It comes when I make the point that you can’t make a fine print from a coarse negative. Most of the negatives that come through the door of my professional printing service are still pretty coarse – underexposed and overdeveloped, burned out highlights and empty shadows with harsh graduation, graininess and poor sharpness.

There are many people who believe that if they can just learn the magic secret, as alchemists strove for the spell that would turn base metals into gold, they will be able to turn out prints with deep luminous detailed shadows, gleaming graduated highlights, and a full rich palette of well separated tones between; that there is some mysterious black art in my darkroom that I hide away from innocent eyes. If only they can learn it, they will suddenly be able to turn their negatives into the glowing prints they envisaged at the moment of making the camera exposure.

Sorry. The answer’s in the negative. Literally. An improperly exposed and developed negative will never make a true fine print. Acceptable, even good, yes. Fine, no. Of course there are those who would like to con us into thinking that there are such black darkroom arts, because it justifies a ‘guru’ position. The current alchemist’s spell is split grading. People are using this convinced that they are uncovering print tones with it that unachievable by simple straight print exposure methods. Wrong. It just takes longer to achieve exactly the same result. But the self-delusion makes it feel good as we wrap ourselves in the emperor’s new clothes.

Sorry, we can perform rescue jobs on inadequate negatives by devices like extreme dodging and burning, condenser and semi-point source illumination, multiple grade printing, preflashing, controlled fogging, latent image pre-bleaching, selective toning and post bleaching to get some kind of result. But thje fine negative prints like a dream without all this hocus pocus, and if we care to apply judiciously a few special techniques to it, the resulting print will shine on the wall as if back-illuminated. We won’t need any of the so-called ‘creative’ tarting up against which I had my rant in Ag magazine.

As I look around I see the four reactions writ large on the faces. Not the Fry’s Five Boys, but the Photo Four Boys.

The first, a tiny minority, look comfortable. They know the system and feel at ease with it.

The second, another minority, are those who prefer to rubbish and dismiss what they don’t understand or can’t do. It’s a sort of photographic xenophobia. ‘Let’s pretend I am superior, then I won’t have to admit my ignorance’. Like xenophobes, they tend to be loudly outspoken and overbearing. We saw a good deal of the same thing among many senior business executives who insisted that their staff use PCs, indeed used IT efficiency to cut staff numbers, yet never had a VDU on their own desk and insisted on shorthand dictation to a secretary for frequently revised drafts.

With the photographic zone system xenophobe, expect to hear him speak disparagingly of zone system users as ‘technical nerds’, ‘zone system techies’, ‘anoraks’ or similar patronising clichés. The only trouble with these people suffering from a superiority complex is that when you actually see their pictures, you realise that they don’t have the right to be patronising about anyone!

The third group of faces is another minority. On these shine disdain. “I am an artist”, the faces silently shout, “and deigning to admit that craft skills can have any place in art would instantly destroy my pseud status. Just let me find a new gimmick to cause shock, and I will be ecstatic”.

Then there’s the rest, the majority. The expressions on their faces hover somewhere between total bafflement, blind panic, and utter boredom.

When I ask, by a show of hands, how they decide what film speed to set on their camera when loading a film, the great majority of the group always let the cassette bar code set it for them on electronically controlled cameras, or they set it from the speed printed on the film box with older cameras. A few don’t. They seem to uprate the speed. It seems macho somehow to do that.

When I ask the group what negative development time they use, they say “what the maker prints in the instructions”. When pressed, most admit to giving ‘a little bit extra, just to be safe’, which actually means, of course, giving ‘a little bit extra just to make things worse’.

Most of the people in the Masterclass room, other than the few committed zone system users, it transpires, have no understanding at all of the link between subject brightness range, film speed, exposure, and development time, and that all these are variables. Many have spent big money on the latest camera systems with ‘deadly accurate’ microchip controlled exposure systems (steadily more sophisticated ways of getting the exposure precisely wrong it seems sometimes).

I spent a lot of money on a camera that takes all the responsibility for exposure and focusing to leave me free to be more ‘creative’.

The Zone system was used 50 years ago by people like Ansel Adams, and he’s dead now.

It’s old fashioned now that we are in the computer age – it’s past its sell-by date – and we can do things better with new technology.

In fact, the zone system needn’t be complicated at all to give a simple practical working method, but I can well understand people being either baffled by it or simply not wanting to pursue their photography through the precise measurements and tables of the more extreme zone system experts, no matter how exact they are.

Even so, the reality is that we can’t choose to work without the zone system. It is simply what actually happens. The only questions are:

1. “Do I understand what is happening?” and

2. “Can I control what is happening to achieve the result I want?”

Trying to pretend that it isn’t happening is a little like a chef saying “I’m going to prepare a great dish, but I don’t know how to cook and I can’t be bothered to learn”. Or perhaps a better comparison might be “I am going to prepare a gourmet meal, but I can’t be bothered to learn how to cook it – I’ll just pop a ready-made meal in the microwave”.

Nevertheless, the reality is that, but for the tiny minority who love, understand and apply the whole zone system approach that puts them in control, the vast majority of monochrome photographers just don’t want to struggle through the learning process. It’s a turn off.

Yet how do we square that with the necessity to have a fine negative for a fine print. This letter came through my Workshop door in January.

“Dear Mr. Thornton, I went to my copy of ‘Elements’ and read the Technical Preface. I have listened to speakers on the zone system, and have read about it over the years and it is becoming more inaccessible with each attempt to understand it. Yet I know I need better negs.” As the lady said in the letter “being a lady of mature years (old in years but very young at heart as it transpired) I feel time is at a premium, so I either give up photography or think laterally what I need is a short cut”.

That made a lot of sense to me. And if I could work out a practical short cut for her, it seemed to me that there would be a lot more photographers out there who would value the method of avoiding all the zone system hassle, yet still get fine negatives.

When I thought about it, the answer was simple, and it is something I use daily as a monitoring device for my own and my clients’ work without another thought. Yet instructing seminars and workshops with many participants constantly shows me how unaware photographers are of this powerful tool to achieve negatives that print like a dream. Indeed, the tool is routinely abused by those who should know much better. What is this magic short cut tool? The contact sheet.

“The contact sheet”, I hear you respond. “I thought you were going to come up with something new and exciting”. Actually, it’s something old and exciting. The excitement comes from seeing for the first time in positive form whether the pictures we visualised at the time we pressed the button actually materialised. And that’s just the problem. We become so involved with the subject matter of the pictures in each frame that we completely miss all the other priceless information the contact sheet contains, and the simple clear answers it provides to our problems without the hassle of zone system testing.

What normally happens when we get a contact sheet from 35mm or medium format made at a commercial processor, or even when we print our own? There will often be different shots made at different exposures in different lighting conditions on the same roll. So that we can see the image content on as many frames as possible, we use the softest grade of paper, give it plenty of exposure, and we maybe pull the print a little if it starts to ‘overcook’. Sure this sloppy method is economic for a commercial lab just wanting to push out as many contacts as it can in a day, and it makes it easier to see what’s in each picture. But it completely loses vital information that would turn ‘microwave man’ into master chef.

Done correctly, what is known as a proper proof contact sheet will give us all the information we need, within the passage of a few films through the camera, to turn out delicious negatives virtually to the standards of the most obsessed zone system freak. Print quality will be transformed for many people.

So how does the contact sheet do this? We start from the simple basic fact that an area of any negative that is clear film base should print as black on paper. In other words, a part of a negative which received so little light through the lens during the exposure of the picture on this frame that, after film development, it shows no silver image at all we expect to be a black area in the resulting print. Note that we don’t say it had no exposure to light, just so little that it did not result in any developed silver density at that point.

Even with no such silver density, the film base will have some small density – nothing is perfectly clear (even, or especially, when a politician claims to make it so!), and the process of film development additionally puts a very thin layer of fog unavoidably over the whole film surface. Therefore even the ‘clear’ area of a negative will have some density i.e. it will slightly reduce the intensity of a beam of light projected through it. That density is not surprisingly known as film base plus fog, and it varies between films and with different developers.

It’s a big thing for zone system workers because, whatever that density turns out to be with a film/developer combination, a figure of 0.1 log density more than film base plus fog is deemed in the zone system to equate to zone 1. Now, don’t get turned off because we have mentioned a number and the word ‘log’, because we don’t need to use these with our contact sheet system. Let’s just understand the importance of zone 1.

The literal foundation to a deep rich satisfying monochrome print with a sense of three dimensional depth, except one intentionally composed of high key light greys, is that it should have the mythical shadow detail. Note that it does not depend on having a ‘good black’ if that black is an unremitting area of unbroken smooth black – this destroys a three dimensional impression. The human eye finds it very difficult to discriminate differences between very dark greys compared to mid and light greys.

When we talk of shadow detail, what this means in a print is that areas in the shadow areas of the original scene that our eyes can see as different shades should be represented in the print as different very dark greys just discernibly different from black. For zone system workers, the first dark area of a scene to be visible in the print as a grey discernible from black is zone 1.

For such an area to print as a grey slightly but discernibly off black, it must have enough silver density in that part of the negative after development. How much is ‘enough’ density? The zone system, as I have said, arbitrarily sets this at a log figure of 0.1. But this is arbitrary. The actual figure will actually vary from user to user according to their camera and enlarging equipment, and their eyes’ sensitivity to subtle changes of near-black greys.

In any case, when we are making a print, and produce a test strip, we don’t read the blacks and greys with a densitometer. We eyeball it. Where it looks right, that’s the exposure we give. And that’s exactly how we use a proper proof contact sheet as practical tool. In fact, while it may seem less ‘scientific’ than densitometer readings, it is actually more so because the densitometer lulls us into a false sense of security that such precise numbers are correct, when we later ignore that numerical basis by making prints by simple eyeballing.

So here’s what we do. If we give just enough exposure through the film base plus fog in contact with the actual make and grade of paper which we plan to use as standard that the paper, after a standard development time in our standard print developer, looks black to our eye, then we have given the ‘minimum time for maximum black’. In other words, if we give any less exposure, the blacks in the print will look visibly grey to our eye.

Note that though the phrase talks of ‘maximum black’, it will in fact be nowhere near any paper’s true maximum black. To achieve the absolute maximum black requires such overexposure that any negative would have its mid and light tones unacceptably darkened, and would have to be developed for so long – perhaps 8 minutes – that fog would begin to lower contrast and quality. No, when we use ‘maximum black’ in this catch phrase, we actually mean the first dark shade that your eyes accept as black.

If we give the whole of a roll of negatives in contact with our standard paper this minimum time for maximum black, then theoretically, in any picture on the roll, any area that we wanted to show as the very first hint of shadow detail should show as a dark grey that your eyes can see is different from the black. If you can’t see it as different, then the negative had too little exposure to give that dark area of the subject enough density after development to print as different from black. Most people are surprised at just how much density it takes in the negative before it will print as non-black. Just because you can see the image in the shadow parts of a negative on the light box, don’t just assume that it will print!

How do we find the minimum time for maximum black for our set up? Set up the contact frame on the enlarger base board, and adjust the enlarger head and focusing bellows so that the pool of projected light covers about four times the area of the frame. Put the frame in the centre of this pool of light. Stop down a couple of stops to get the most even lighting you can over the frame area.

Insert the film and paper in the frame, and make a test strip on your standard grade of paper. (That might be grade 2 for graded or 2½ for VC. Some people find thinner negatives and grade 3 better for 35mm). But don’t make a test strip of the images themselves, use the clear film base plus fog of the film rebates. With 120, it is usually easy to place your test strip across the divisions between frames. With 35mm, use the sprocketed edge. Sheet film users can use the edge too. Be careful with the ubiquitous and excellent Paterson contact frames – the transparent plastic overlay on the glass that grips the film edges has density and will result in a false test strip reading if you don’t move one strip of 35mm film out from under this plastic overlay so that it lies on the paper under clear glass only. Once the correct exposure is found, you will slot it back under the plastic for making the full contact sheet.

Choose a suitable time, perhaps two seconds, to use as test strip steps, or you can use f stop fractional divisions for constant density changes if your timer has the facility. Make the test strip of the clear film base plus fog. Develop, stop, fix, and wash in ag completely standardised way that matches your normal working routine. With RC papers, and working at the shadow end, dry down isn’t an issue, but it is easier to view and judge a dry test strip, so you might want to do that for this exercise.

Now examine the test strip under the same viewing light you would use for assessing the test strips of actual prints (which should, incidentally, match the light under which they will be displayed). You are looking for the first step in the test strip which appears black i.e. you will not be able to discern the next step as different from it.

The first step which reaches black may not be easily apparent, especially if your test strip steps were fairly finely spaced in exposure time terms. You have to train yourself not to look at the pictures next to the clear film. The test strip step lines which run across the picture frames can be translated by the eye into a line across the edge black area which is not actually there. The ability to see or not see the sprocket holes helps with 35mm, but with all formats covering the picture areas with a couple of sheets of white paper helps to clarify the decision about the correct minimum time for maximum black. I also find it helps sometimes to view the test strip with transmitted light for a few moments on top of a light box, then switch off and decide under normal reflected light.. However, make your decision with your own eyes.

Once you have decided what this is, you have a standard time which you can apply with this film/developer/paper set up. Mark the enlarger column/ focusing bellows position so you can return to it. Note that if you ever change anything in this standard line-up (e.g. a new box of paper) you will need to do a new test strip.

Now using this minimum time for maximum black exposure, make your full contact sheet processed in the standard way. Be careful how you give the exposure. If, say, you found the time on the test strip to be 5 two second steps, do not give a ten second contact sheet exposure. This will give significantly greater exposure. Give the same 5 two second bursts of light. Process as standard. When the contact sheet is washed and dried, examine it under the same viewing light.

Let’s first look at the overall sheet rather than individual pictures. What we are looking for first is the shadow detail i.e. are the darkest areas in the pictures generally where we wanted to see some detail just discernibly different from black? School yourself – ignore the middle and high tones at this stage.

If the shadows are mainly all black when there should be some detail, you have generally underexposed the negatives. This means the film speed is wrong for your technique and equipment. If the shadows are very dark you may be using a film speed double or even more what it should be i.e. 1 to 1½ stops out. This means that a film nominally of EI 400 should actually be re-rated at 200 or 160. If the shadow darkness is less marked, your true film speed may be only 50% = ½ stop out, say EI 250.

If generally the shadow detail is too light, you would need to make the opposite corrections. This would be extremely rare in my experience. Most people carrying out this test for the first time find they need to drop their film speed rating by about 1 stop.

If the shadow detail is generally OK, but there are just a few shots where it is low or missing, this means that your film speed rating is actually OK, but that your metering technique is letting you down in the particular circumstances of the defective pictures. Often this will be down to including a lot of sky in the metered area of the picture, or to a scene with an exceptionally high subject brightness range – that’s one where the difference between the brightest part of the scene and darkest part of the scene pictured are especially great.

This might be with harsh directional sunlight and deep shadows outside, or an interior scene with an external window in shot for instance. Just by looking at the ‘failed’ exposure pictures you very easily and quickly learn the type of scene where you will need to intervene and correct metered exposure, and by how much. Usually that means taking an exposure reading of the darkest area in which we want to see full textured detail – for instance the grass in the sharp-edged shadow cast obliquely by a rock or tree – then stopping down 2 stops from the reading given. Zone system aficionados would tell you that’s the equivalent of placing that area of the scene on zone III.

Now let’s ignore the shadows and look at the highlights. There’s an old photographic catch phrase ‘expose for the shadows and develop for the highlights’. Most people have heard it but many don’t know what it actually means. The following is an over-simplification, but it will serve for the sake of clarity. The film density that was needed to show that shadow detail as just different from black is purely the function of the amount of exposure given to the negative, and is virtually unaffected by film development time. The highlight density of the negative, i.e. the darkest heaviest parts of the negative, are controlled almost solely by the development time.

Imagine that you were hanging a curtain on a rail. Getting the first hook on to the first fixed ring at the start of the rail is the equivalent of exposing enough to place the shadow detail just above black. Now all the other hooks are placed into the rings lined up next to the first fixed ring. These are all the other greys from dark, through mid, to light in sequence. This is what happens at the very start of development. As development proceeds, the curtain gets drawn along the rail gradually spreading out the rings until the furthest hook and ring, the equivalent of the negatives densest highlight, reaches the end of the rail.

This is the equivalent of the negative’s brightest highlight becoming so dense that if it were given the same minimum time for maximum black exposure to paper on our contact sheet, it would print as pure paper base white – just. Any less development would allow it to pass just enough light to show on the print as a light grey only just discernible from white.

Of course if we were to continue drawing the curtain further, that is to continue developing the negatives, more and more of the hooks/rings would stack up at the white end of the rail. Effectively, this would mean that areas in the pictures that we expected to see as different light greys – clouds in a landscape for instance – would all get bunched up with the furthest white hook/ring, and thus simply print as the same blank white. We term this ‘burned out’ highlights.

If we try to rectify this by burning in the area in the subsequent print, or by switching to a lower contrast paper, the highlights will print, but the hooks/rings are still all pressed together resulting in a virtually flat light grey area with virtually no separation between the light grey tones as we saw them in the original scene. Additionally, such areas are inevitably mottled and over-grainy in comparison with a negative where the curtain was drawn – the negative was developed – just enough to place the very brightest highlight on white while leaving the other rings/hooks spaced out along the rail.

If we for some reason underdevelop – don’t draw the curtain far enough for the furthest hook/ring to reach white – the problem is much less. By stepping up contrast grade of paper, we can make that furthest hook/ring reach white, but the other light grey hooks/rings will still all be spread out. So when printed they will still show separation and smooth graduation. Grain will be less, even on the harder paper, and sharpness will be higher.

As I said this is an over simplification for clarity’s sake, but it is essentially what happens.

As we look at the contact sheet generally now examining the highlights, we look to see if the areas that we expected to see as light greys just different from white do in fact show like that. If, generally, they are actually pure white, it meant we developed the film too much. If, generally, there aren’t pure whites where there should be – the brightest highlights are too dark a grey – it means we underdeveloped.

Underdevelopment can be apparent in, for instance, studio portraits with soft box and reflector lighting. But my experience with thousands of customer orders for prints is that the vast majority of negatives have been over developed quite significantly. When contacted, the clients tell me that they have simply followed the manufacturer’s development times. It is almost universal that times need to be cut back, and substantially. There could be many reasons for this. One of them is that photographers like to take pictures of scenes that exhibit a far greater subject brightness range than the film/developer maker sets as normal.

So let’s look again at our contact sheet’s highlight regions. It may be that generally the highlights are not burned out, but that they are on just a few frames. If we look at these frames, we can soon see what sort of lighting conditions gave the over-wide subject brightness range where we need to reduce development. It is surprisingly easy to begin to recognise these subjects automatically and instinctively when in the field with the camera.

So what do we do when we know that we have just a few such high contrast frames on a roll when the rest are of normal contrast? The rule is to reduce development to match the most contrasty shot on the roll (use of two bath and tanning/staining developers such as my own DiXactol help too). Remember, once the highlight curtain rings/hooks are squashed together, they stay like that. If they aren’t drawn far enough on some frames, we can always step up the paper’s contrast to push them up to the end of the rail = proper brightness in the print.

Remember earlier I mentioned “expose for the shadows, develop for the highlights”, and said that exposure solely controlled the shadows, while development solely controlled the highlights? Well, I told lies. But they were white lies. The claim is basically true, but it needs to be a little flexible. Development time has a much greater effect on the highlights than the shadows, but it does have some effect on the shadows.

Most people using this contact sheet control system will find initially that they need to cut their development times. You do this by a simple trial and error system. For all films other than T-Max, start with a 20% development time cut (10% for T-Max), but reduce your film speed from your normal rating by ½ stop for each 20% (10% T-Max) development cut you make. Within 2 or 3 films with your contact sheet monitoring you will have homed in on the right speed rating and development time for your film with your technique and equipment.

Note that as you reduce the development time, you may find that the film base plus fog density may reduce, and you may need to retest to find a new minimum time for maximum black contact exposure, but this should only occur if you are making large development time reductions. Don’t be afraid though if you do find yourself making big development time reductions. It is not uncommon to find 30 – 40% reductions for some people.

That’s it really. That’s all you need to do to obviate all this zone system stuff. It’s a lot quicker to do than describe. Setting it up in the first place is simple and quick. After that, since we all make contact sheets, or should, there is no extra work involved. Any unannounced changes to film, developer, paper etc. by manufacturers (no, they wouldn’t do that would they!) are immediately apparent. Bracketing, beloved of both camera and film manufacturers, who see us wear out our camera three times faster, and use three times a much film, is a thing of the past. We feel in control and know what we are doing and why. The confidence shows in our pictures, and the negatives print like a dream without the over-hyped black arts of the printer. We emerge from our dark room satisfied and inspired instead of frustrated. It can’t really be that easy, can it? Well, no actually.

At this very moment, zone system zealots are preparing to plunge their knives, edges glinting with zone XII specular highlights into this contact sheet system triumphant at discovering its key flaw. It’s quite simply that it is a contact, not a projection print. You see once we put a negative in the carrier and project it through the enlarger lens it gains contrast compared to a contact sheet by the so called Callier effect – right?

Er, no.

In fact, with today’s preponderance of colour and VC enlarger heads using a light mixing box and diffusion, the difference in contrast between the contact and the projection print is insignificant. You can safely ignore it. Any tiny differences can swiftly and easily be corrected by a tiny tweak of the contrast grade of paper.

With the few condenser heads in use today, it is true to say that there is a big contrast difference between contact and projection print – typically one paper contrast grade. Still, that’s not much of a problem. We simply allow for it in contacting. If our normal grade for actual printing is, say, 2 we simply contact at grade 3. It won’t be exact, but it will be that close that the difference won’t matter. If in doubt always reduce development a little, remember. Within 2 or 3 films contacted then printed, you will be able to tweak the grade at which you contact, or simply get to know the kind of look a contact has on grade 3 that will projection print well on grade 2.

Of course, all this imprecision will be anathema to zone system zealots who insist on the exactitude of densitometer readings. They fool themselves. There is an inherent imprecision in selection of areas to meter in an original scene; in the necessity to work in, usually, ½ stop steps; processing temperature control and water quality variations, among a host of other variables.

I use and value the zone system, but am not blind to its limitations. In practice, for the average photographer, the contact system works really well. Try it.

THE ZONE SYSTEM

Many photographers setting out on the discovery of fine printing make the mistake of thinking that to be a fine print, the photograph should have strong black shadows of the maximum density the paper can yield. And not just beginners. I well remember listening to a lecturer at a Royal Photographic Society distinctions workshop for would-be Associates perpetuating the hoary myth that to get real print quality it is necessary to keep print developer temperature well up – say 24’C – and give a full 3 minutes development.

The only result of this is to give extra density across the tonal range and possibly to veil the highlights and give a muddy print. It also tends to inhibit toning and add to the chance of fog veiling, especially if toning is then prolonged. A richer print always results from the velvety subtleties of shadows away from maximum black, even if the absolute black is not as dense in objective measurement as flat maximum paper black shadows. In any case, I do not believe that the human eye can usually distinguish the difference between deep blacks, such as between print densities of 2.0 and 2.1, whereas it can far more readily discern this degree of difference in the highlight region.

The question, then, is how do we achieve the desired tonal rendition in the final print. Obviously a normal monochrome picture has a seamless range of shades from deepest black to paper base white – an analogue effect. If the paper white reflected almost 100% of light and the maximum black virtually 0%, then the ratio of the range of tone reflectance possible would be about 100:1. Obviously such perfect reflectance and absorption doesn’t exist and the ratio is really far less – 80:1 would be reasonable. Yet the range of brightness of light reflected from the average scene will rarely match this. Occasionally it will be less, as in a scene with subject matter of similar tonal value when reduced to grey under flat shadowless lighting. Far more frequently it soars above it, and it’s almost guaranteed in any landscape with sky.

|

| Loch Arklett Image (c) Barry Thornton |

It certainly was in the case of the Loch Arklett photograph here (ABOVE – Heat Haze, Loch Arklett 1991). The picture reduces the highlights into discrete areas. It depends on the subtle separation of the lighter tones and on their being free of the mottling produced by burning-in heavy negative densities – a different phenomenon from prominent grain, though I believe that grain would have spoiled this image. The original scene didn’t ‘feel’ grainy. The only reliable way I know of realising in the print the picture I had visualised at the time is a method of exposure adjustment and development control known as the zone system.

I was using my beloved Rollei SL66 with its back loaded with Agfa APX25 rated at EI (Exposure Index) 12. (In another page on this site, I explain how to decide what film speed rating to use.) With the 250mm Sonnar mounted to compress the distant elements of the picture, I needed f/16 to give adequate depth of field. A spot reading of the sky above the mountains showed a light value of 17, which meant a shutter speed of 1/60 at this aperture.

However, the near shadows gave a spot reading of light value 8, i.e. 8 seconds at f/16. That’s a nine stop difference between the shadows and the highlights in both of which substance was required to avoid a ‘soot and whitewash’ effect: shadows devoid of details and bald white high tones. Since each stop extra exposure gives twice as much light, it’s easy to work out that the subject brightness range, increasing in the series 2, 4, 8, 16…, reaches 512:1 at nine stops. (Each stop difference for shutter speeds is calculated by halving (or doubling) the time. So starting at 8 seconds, one stop less is 4 seconds, two stops is 2 seconds, and so forth. Using conventional shutter speeds, the range for the Lock Arklett scene was 8, 4, 2, 1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/15, 1/30, 1/60 – a difference of nine stops).

But this has to be shown on a paper with a reflectance range of perhaps 80:1, so something has to be squeezed. Significantly, if the range had been only six stops, that would have been 64:1 – somewhere around the reflectance range of the paper. Film manufacturers seem to assume an average scene brightness range of about five stops showing detail when they specify their film’s speed and its normal developing time. Both would be wrong for this picture. If we split the ‘analogue’ continuous range of greys up into ‘digital’ steps for this picture, we could use the nine stops as the discrete steps. If, for simplicity, we say one stop less at the shadow end gives total black, and one stop more at the brightest end gives maximum paper white, we have a scale of 11 steps from black to white, with nine steps of grey in between where each is representing a step in the original scene twice as light as (i.e. one stop less than) the previous step.

These 11 steps are called ‘zones’ and, by convention, they are given Roman numerals, where 0 = featureless black and X = featureless white. Please note that these are the real brightness values of the scene, they are not the greys used to represent them on a paper print. These are obviously compressed to get within the reflectance range of the paper. By convention print greys are known as ‘values’ rather than zones. It is important to realise that, for all practical purposes, black is black in both scene and print, but not so white. Paper can only give its reflected white as the lightest value in a print, but the original scene may well have had radiant light sources, such as the sun, or specular reflections of the light source, such as water, snow crystals, glass, polished metal etc, which are very much brighter than paper white. Yet these all have to be convincingly depicted within the confines of the paper.

And what gives the maximum conviction is what fine photographs are all about. A blank paper white for all very bright zones, which can easily extend to XII or XIII, is not convincing or attractive, no matter how logical. On the zone scale, zone V is the standard 18% reflectance grey to which all exposure meters are nominally calibrated (actually, some meters aren’t calibrated to 18% grey, but let’s assume they are for this discussion). This means that if they are pointed at a scene they will assume that it is ‘average’, that a purée of all the tones in the scene will be this 18% grey.

Sometimes this is true. If it isn’t, manufacturers like Kodak provide 18% grey cards to meter in the same light as the scene to correct this. A meter will always try to turn what it sees into zone V grey regardless of whether it is black, white, or any grey in between. If it reads black for instance, zone 0 on our scale, it would indicate five stops over exposure to turn it into zone V grey. The Loch Arklett scene happens to average out about zone VI, so the meter’s indicated average exposure would have been one stop over.

But average would not be good enough. The mean zone with average reading is always V whether the range of subject brightness is the film-makers’ assumed norm of five where detail is required, or the actual nine in this picture. This means that if I had exposed as indicated by an averaging meter (including an incident meter, or any meter pointed at a standard grey card in this scene), then developed as recommended by the film maker, I would have a negative where the bottom two stops of shadow tone value would drop below the dark grey that would reveal detail into near or full black, while the top two stops of highlight tone value would be pushed over the lightest grey into paper base white. So the print would have solid black shadows and stark white highlights where the viewer’s brain knows there shouldn’t be. In other words, the print would appear harsh and contrasty.

In fact, zone I reproduces as a print value so little different from black that were there not an actual maximum black next to it for comparison the eye could not discern the difference. At zone II, the print value grey is significantly different from black, but not enough to be able to define anything but a hint of detail in the shadows. It takes zone III before full shadow detail begins to show in the print. At the other end of the scale, zone VII is the last in which full highlight detail can be shown in the print. Zone VIII shows a very light grey with a hint of detail, and zone IX the slightest trace of off-white grey, indistinguishable from white unless pure white is placed next to it.

In this picture, being able to visualise the print value grey of each zone through practise, I decided to place the deep shadows of the near bank on zone II. This meant I took a spot reading of them, then decreased the indicated exposure by three stops (remember, the meter always indicates the exposure for zone V = three stops more than zone II). This gave me an exposure of 1 second at my desired f/16. The average reading would have been two stops less at 1/4 second.